On the Significance of Creating Ideas and Judgments

from Individual Creativity and Initiative

plus a Conclusion on what Is Important

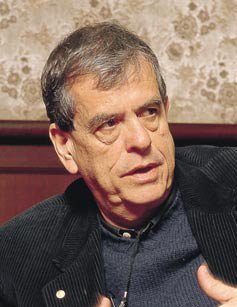

| Aaron Ciechanover | |

| 1974 | M.D. The Hebrew University |

| 1981 | Ph.D.Technion-Israel Institute of Technology |

| 1992-present | Full Professor, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel |

| 2004 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry |

| |

| Dr. Ciechanover | |

Although we respect all the languages such as Japanese, Russian, German, French and Hebrew, we should accept that English is the language of scientists in today's world. We should adopt the language and speak it fluently, so that we will be able to communicate.

This has nothing to do with the wish of any nation to keep its own language for literature, journalism or anything, but I think the idea that all we scientists use one language is a good idea. It happens to be the English language, but it could have been Hebrew, Japanese or German. Somehow after World War II, the English language became the dominant language in the scientific world because of America. It has nothing to do with national pride, however. We all speak national languages. Still, it can be said that for science, the best way to communicate is in one language. In science, all the important journals are written in English, be it physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, or economics. Therefore, we ought to speak it fluently and in depth, so that we can understand all the subtleties of the language. However, at home, in our own theatre, poetry and the arts, we should keep our national languages. It is not entirely exclusive.

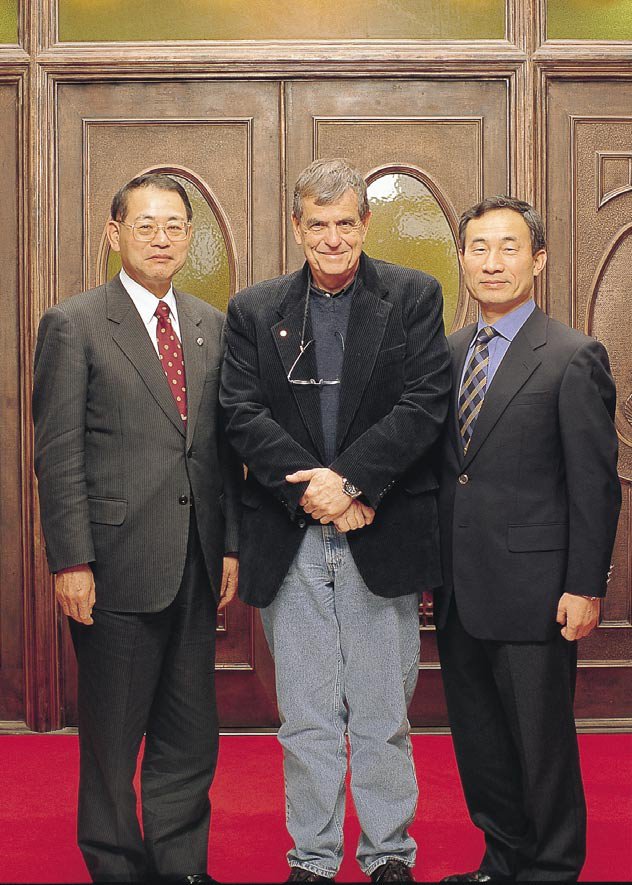

MC: This is coming rather belatedly, but I would like to congratulate you on your receiving a Nobel Prize. President Kajiyama and Professor Fujiki are also eminent scientists. I would like to ask you what it was like to see a breakthrough in your research or your discovery bearing fruit. What did you feel when you noticed that your work was bearing fruit? Do you think there is a certain way one can achieve that?

Dr. Ciechanover: Well, I don't think there is a moment in which all of a sudden black is converted into white. It is a gradual process. But it started with an idea, when I was a graduate student. At that time, we didn't have any thought of prizes nor big achievements. We are just a sort of small country and a small group of scientists. Therefore, we should not aim at competing with big sharks. This was one idea, to keep away from the mainstream. This is maybe an idea for anybody who wants to be original. In the mainstream, you will find a big highway where many people are driving. Maybe it is better to take a side road where the traffic is not yet congested. That is why we took a side road. At that time, scientists were going especially after DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis, and nobody noticed that all the proteins have to be degraded at the end. Therefore, we decided to go to the other side to the gdestructionh side. This strategy was our advantage, because for seven years nobody really noticed that we were there, which gave us opportunities to lay down the entire system without even one eyebrow being raised by big American sharks or any other sharks. Thus, we had no competition for eight or nine years, which is really rare these days. It just doesn't occur anymore. But it may occur again. If people pick up on something which is peculiar but important, they may find the scientific community not competing with them.

|

| Dr. Tisato Kajiyama, President Major: Polymer Chemistr |

Dr. Ciechanover: Well, again it was a gradual process. But the first occasion which required imagination and inspiration was in picking a subject. We had to pick something that was (1) important and (2) not competitive yet in order to not be in the main stream. This was Rule Number One. Then, obviously, it took a lot of imagination, in the sense that we were not to be caught up in any paradigm. In short, the idea is not to be limited by any paradigm. I don't want to go into technical details. I'll show you instead how we departed from a paradigm, because once you get to a crossroad you have to decide one of two things. Is there something very new here? That is sometimes very difficult for people to figure out. Or, on the other hand, is there something here that is not right? Then you go back to traditional thinking. The idea is to make a distinction between something very new and something wrong and to decide when it is new and when it is wrong. I think this takes both imagination and courage. Human beings are conservative, and in science we should be very careful to find a balance between conservatism and imagination and breakthrough. We should not let conservatism be dominant in science.

President: I myself am a chemist. I believe science needs flexible attitudes and very good observation. In the process, you also need to add imagination at the appropriate time. I think that is the way to develop science. Science is, in a way, making conventional common sense into unconventional common sense. In order for that development to be achieved, scientists should not stick to the existing common sense, as you point out.

Dr. Ciechanover: Yes, I completely agree.

Professor Fujiki: I also agree with President Kajiyama. I am a bio-scientist. This is what I often hear from Nobel scientists like yourself. When you are engaged in some kind of research, sometimes you may come across unsatisfactory results. You should not discard the results then, however. You should keep them at least overnight. Then if you look at them with a fresh eye, you may find something new which has not been discovered before. My professor, Dr. Christian de Duve in the Unites States, for example, was not satisfied with the results of some tests one night, but he did not stop there and kept them overnight. When he looked at them afresh the next morning, he discovered that a subcellular organelle, called lysosome was related to this kind of result. We tend to assess a result based on conventional common sense and easily discard it if it is not satisfactory. For young students, gtrue or falseh type questions and memorization may be important. More importantly, however, I would like them to have flexible minds. You may think a particular result is an error, but you have to analyze it carefully without being bound by conventional thinking so as to advance into the next stage. The importance of such flexibility has been proven in the field of bio-science.

Dr. Ciechanover: Let me add one more point, which is very important and maybe a little bit subtle and general. As a guest in Japan, I admire this country for many good reasons. If fact, I shall be doing my second sabbatical here, when I come here again next year. Israel, however, somehow chose a different system in order to run its science. Maybe it is because Israel is young. We are not bound to any tradition. We have a long history, but as a modern country we are still in infancy, at only 57 years old. When we established our university about 60, 70, or 80 years ago, we decided to adopt the American system. For better or worse, the American system says that everybody is independent. In that system, you bring in a young professor, give him a bench and some money, and tell him to go to work on his ideas. He is not working for anybody. He is working only for himself. In six or seven years, he is up for tenure, a permanent position. He is being judged only by his achievement. His imagination and his ability also occur independently through his science.

|

| Dr. Yukio Fujiki, Professor(Cell Biology), Leader of the 21st Century Program |

President: I also agree with you, Dr. Ciechanover, since I also have the experience of studying in the Unites States. I think this system has been successful for about 95% of the time. The question is how about the remaining 5%. Science sometimes requires group work. X-ray crystallographic analysis is one example, which has been given up in the Unites States. X-ray crystallographic analysis seems to be a special area for Japanese researchers these days. It is very much owing to the chair system which Japan adopted. In that system, students study under one professor. What I would like to point out here is that we have to think about the nature of research.

Let me add one more thing. It has been about 100 years since national universities were established in Japan. At the time of their introduction, we introduced the German system, which is the chair system. While it has both good and bad points, Kyushu University is still run basically under this chair system. As the president of the university, I regret to tell you that we have started to notice some of the adverse effects of this system. It is difficult to change the system. Therefore, I had to think about alternative ways of encouraging individual researchers. Under the chair system, professors procure grants for research and allocate grants to each of their junior researchers. This, however, can spoil the researchers. Then, the researchers gradually stop obtaining grants aggressively by themselves. In this sense, I personally believe it is important for young scientists to be independent from their professors. To this end, I have decided to come up with an initiative called thegResearch Superstar Support Program.h Under this initiative, approximately 40 researchers are chosen among those who have produced good results to encourage their research at an individual level.

Dr. Ciechanover: I am fully aware of the Japanese system, maybe much more than you can imagine. I have been in this country for almost a year altogether. It does not have to copy the American system. Every country should adapt according to its own needs. In addition, you should not make a revolution overnight, because it becomes bloody. We don't want to destroy the system. It is true that for the remaining 5%, as you mentioned, our efforts have to be made in groups. The individual scientist cannot do everything by himself. He needs a group around him. In the end, however, we should not lose sight of the targets. The targets are independence and freedom of thinking. And if this is all clear, everything is clear.

| Talk with Nobel Prize Winner, Dr. Ciechanover |

|

Professor Fujiki: What do you think about this point, President Kajiyama? Let me give some comments as a bio-scientist. In Japan, the government has come up with many initiatives including the promotion of education to encourage students. These are intended to educate young people to be competent not only in the field of science but also in industry. But my own impression is that recipients of this service are not reacting as actively as expected. We have grave concerns about young people just waiting for instruction to be given to them. They lack a sense of enthusiasm. They seem to regard it as more important to enjoy everyday life. As a bioscience professor I really worry about the future of Japan. Although the government has prepared many good systems to benefit students, students themselves are not responding properly. Now I am aware of our own responsibility as teachers, and we are committed to making further efforts to improve these situations. I think that the fact that Japan became an affluent country economically triggered this tendency. However, I don't feel that one dollar is equal to 100 yen. A dollar can be worth two or three times that much, judging from the current state of things. Praised to the skies, the Japanese people are self-content. I don't think this trend will be allowed to be tolerated much longer. I always try to whip up the enthusiasm of my students in the classroom, but it just seems to slip out of their heads. This is the dilemma we now face.

President: In addition, in terms of education in Japan, we lack the custom of encouraging children to ask questions. It is very important to encourage them to learn the joy of asking questions. I think it is also important for young people to pay more attention to the surrounding situations and changes occurring around them, and to have their own opinions about these changes. These could be changes in nature, the townscape, politics, or the economy. If they have their own opinions, it will lead to the cultivation of their own individuality, which then leads to originality and, in the end, creativity. I think Japan lacks those two points. In contrast, people in the Unites States have these habits. Children in America know the joy of asking questions and have their own ideas. I think that is the case in Israel, too. May I ask you whether you have these kinds of human development initiatives in Israel?

President: In addition, in terms of education in Japan, we lack the custom of encouraging children to ask questions. It is very important to encourage them to learn the joy of asking questions. I think it is also important for young people to pay more attention to the surrounding situations and changes occurring around them, and to have their own opinions about these changes. These could be changes in nature, the townscape, politics, or the economy. If they have their own opinions, it will lead to the cultivation of their own individuality, which then leads to originality and, in the end, creativity. I think Japan lacks those two points. In contrast, people in the Unites States have these habits. Children in America know the joy of asking questions and have their own ideas. I think that is the case in Israel, too. May I ask you whether you have these kinds of human development initiatives in Israel?

Dr Ciechanover: Well, President Kajiyama raised two extremely important issues. One is general, while one is more confined to Japan. Let me relate to each of them.

Dr Ciechanover: Well, President Kajiyama raised two extremely important issues. One is general, while one is more confined to Japan. Let me relate to each of them.

One issue has to do with general attitudes of young people. We are facing the same problem. Even Americans are facing the same problem. They lack initiative, lying back and just waiting for some miracle to happen. We are spoiled in Western civilization. The only people, I think, on earth who have not suffered yet, but may suffer in the future, are the Chinese. They will probably become the next American or next Japanese as far as the future of industries and high-tech fields are concerned. Ultimately, however, they could also suffer from this disease. Actually, the Chinese are now starting to dominate American markets. They are becoming professors and researchers, taking the places of Americans themselves in American universities.

But what can we do about this? Well, there is no magical solution except for hard work. In Israel, I am not sure how successful it is going to be, but we have decided that this problem has to do with basic education from kindergarten. In order to start such education, you also need very good teachers. And good teachers need good salaries. Because teaching in elementary schools and kindergartens has become a second grade profession, people don't want to become teachers. So it is a problem, and parents are complaining. We need to bring teachers back to their former status found in the world of 300 years ago: a respected profession with a high income. Then, very good people will be attracted to educating the young generation.

This is not a problem of universities alone. Universities always get the products of 12 or 15 years of education: three years of kindergarten, six years of elementary school, and six years of high school. In short, universities could do something, but they cannot do a lot. The products we are getting at universities have already had 15 years of education. If we do not change this education system, the universities will not be able to do as much as they want.

We have to convey a clear message to the young generations and their parents. At the same time, education goes hand with hand with high incomes, a high social status, and a high level of health. The more income we have, the more education we have and the healthier we should be. The more income we bring to our families, the better our situation will be. It is clear that uneducated people belong to low income layers of the population. With education, I hope this problem will be resolved. It's not just your problem, so don't worry. We are in the very same pot.

MC: Lastly, could you please give a message to the students of Kyushu University and young researchers?

Dr. Ciechanover: This is applicable not only to the students of Kyushu University, but to all students and young researchers. Be yourself. Think independently and challenge your professors. Don't take anything for granted. As you said, don't be shy, and ask interrogative questions.

All: Thank you very much.

(This interview took place on February 22, 2005 in the Room for honored guests of the Administration Bureau.)