Culture Cafe

Finding Friends at the Culture Cafe

For foreign students in Japan, meeting

Japanese students can be surprisingly

difficult. I have experienced this

difficulty first-hand while attending

Kyushu University. As an exchange student

following the typical pattern of most

foreign students in Japan, I too lived in

the dormitory for international students

and took the usual language and culture

classes. However, unlike most students

who return home after a year or two of

study, I chose to stay and enter the

Masterfs Program in Human-

Environment Studies. It was from this

time that I decided to apply what I had

learned in environmental psychology

toward solving a problem I sensed as

both strange and very unfortunate: international

students at Kyushu University

had stopped looking for Japanese

friends.

The Kyushu University International

House was where I first gave up looking

for Japanese friends. I lived there during

my first year in Fukuoka, and yes, I

did manage to make a number of new

friends from my tiny, one-person room

on the first floor of the (then) all-male,

five-story gBuilding E.h There were the

other American students, all strangely

bunched on the upper floors of the same

building. Most of them were here for just

one year, for a year of study abroad.

Then there were my Korean, Chinese,

and Brazilian friends, just to mention the

nationalities that stand out most in my

mind. They were scattered throughout

the many buildings of the International

House, and though it was often difficult

to keep track of where everybody lived,

we always managed to keep tabs on

each other in our new, closed-knit community.

There were, however, a couple of

Japanese students living in the

International House as resident assistants,

but they were graduate students

with many time restraints, and we

learned not to expect them to attend all

the parties and other social gatherings

we had. As for the many undergraduate

students of Kyushu University who may

have wanted to come to the International

House to make new friends or join a

party, most either didnft have a car or

couldnft afford to visit on a regular basis.

And though I had found a few friends in

my research group with whom I could

talk, I nonetheless found myself speaking

Japanese most with the other foreign

students in the International House

rather than with Japanese students.

That year I sure learned a lot about the

Korean Peninsula and Nisei lifestyles in

Brazil, but I was still in the dark about

how our Japanese neighbors lived. No

people, no communication.

The second place I had to give up

looking for Japanese companions was at

the International Student Center (ISC),

which is the building where almost all

new foreign students take Japanese language

and culture classes. I was no

exception, taking kanji and grammar

classes my first year. Again I found

myself surrounded by my International

House neighbors. We even parked our

bicycles in the same place. Of course

there were some faces I didnft know, but

one characteristic had not changed:

there were no Japanese students here.

And they never came. I sometimes

would see some Japanese students

hanging around the first floor of the ISC,

but a little eavesdropping would quickly

reveal that they were there specifically to

hear a speech (there is a large auditorium

on the first floor) or to sit through an

orientation for their own future study

abroad adventures. This was merely a

transitory stay, a brief stopover during

their academic journeys, and thus we

never saw them again. Again, no people,

no communication.

In 1998, my first year of graduate studies

at Kyushu University, I was given the

opportunity to change this situation of

being alongside, but not with, Japanese

students. I got together with a group of

classmates from my department, and

armed with some funding from the

Kyushu University Venture Business

Laboratory, we brainstormed for ideas

on how we could make our campus

more enjoyable and conducive to communication

among students, especially

to communication between foreign students

and Japanese students.

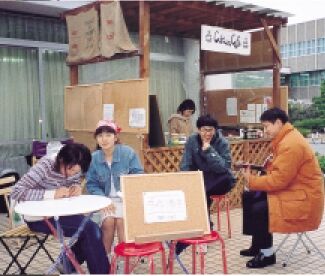

What we came up with was simple

yet creative, new yet familiar: a coffee

shop. We built an outdoor cafe directly

on campus that provided everyone the

opportunity to enjoy inexpensive coffee

or tea in an open atmosphere, free of

any departmental affiliation or label. We

named it the gCulture Cafe,h to express

its function as a coffee shop while

encouraging a wide-ranging mix of

social exchange among students from

various cultural backgrounds. In addition,

by having all cafe staff positions

filled by students, we ensured the cafe

would remain elocalf and not appear foreign.

These staff were mostly undergraduate

students from a number of

departments, including engineering,

education, and agriculture. Working

hours were flexible, and there was

almost always an interesting mix of foreign

and Japanese students working at

any given time. As for the customers,

not only a variety of students, but also

professors, librarians, cafeteria workers,

and even local citizens, who were not

directly associated with the university,

became our regular customers.

What we came up with was simple

yet creative, new yet familiar: a coffee

shop. We built an outdoor cafe directly

on campus that provided everyone the

opportunity to enjoy inexpensive coffee

or tea in an open atmosphere, free of

any departmental affiliation or label. We

named it the gCulture Cafe,h to express

its function as a coffee shop while

encouraging a wide-ranging mix of

social exchange among students from

various cultural backgrounds. In addition,

by having all cafe staff positions

filled by students, we ensured the cafe

would remain elocalf and not appear foreign.

These staff were mostly undergraduate

students from a number of

departments, including engineering,

education, and agriculture. Working

hours were flexible, and there was

almost always an interesting mix of foreign

and Japanese students working at

any given time. As for the customers,

not only a variety of students, but also

professors, librarians, cafeteria workers,

and even local citizens, who were not

directly associated with the university,

became our regular customers.

In this way, what began in 1998 as a

pipe dream for an adventurous group of

students had become a prominent campus

feature by the year 2000. Though

only a small-scale project, I believe the

Culture Cafe takes an important step

toward improving the communication

gap between Japanese students and

international students by providing a

pleasant place for snacks and social

interaction on campus. As William H.

Whyte notes in his book, The Social Life

of Small Urban Spaces, gFood attracts

people who attract more people.h I

believe it.

By Chad Walker,

1st Year Ph.D. student, Human-

Environment Studies, Kyushu University

Previous

Page Top

Next

What we came up with was simple

yet creative, new yet familiar: a coffee

shop. We built an outdoor cafe directly

on campus that provided everyone the

opportunity to enjoy inexpensive coffee

or tea in an open atmosphere, free of

any departmental affiliation or label. We

named it the gCulture Cafe,h to express

its function as a coffee shop while

encouraging a wide-ranging mix of

social exchange among students from

various cultural backgrounds. In addition,

by having all cafe staff positions

filled by students, we ensured the cafe

would remain elocalf and not appear foreign.

These staff were mostly undergraduate

students from a number of

departments, including engineering,

education, and agriculture. Working

hours were flexible, and there was

almost always an interesting mix of foreign

and Japanese students working at

any given time. As for the customers,

not only a variety of students, but also

professors, librarians, cafeteria workers,

and even local citizens, who were not

directly associated with the university,

became our regular customers.

What we came up with was simple

yet creative, new yet familiar: a coffee

shop. We built an outdoor cafe directly

on campus that provided everyone the

opportunity to enjoy inexpensive coffee

or tea in an open atmosphere, free of

any departmental affiliation or label. We

named it the gCulture Cafe,h to express

its function as a coffee shop while

encouraging a wide-ranging mix of

social exchange among students from

various cultural backgrounds. In addition,

by having all cafe staff positions

filled by students, we ensured the cafe

would remain elocalf and not appear foreign.

These staff were mostly undergraduate

students from a number of

departments, including engineering,

education, and agriculture. Working

hours were flexible, and there was

almost always an interesting mix of foreign

and Japanese students working at

any given time. As for the customers,

not only a variety of students, but also

professors, librarians, cafeteria workers,

and even local citizens, who were not

directly associated with the university,

became our regular customers.