Most people have heard that children learn language amazingly quickly. Because many Japanese understand that knowing English is increasingly a useful skill, and because they think that children always learn languages better and faster, many forms of English education for children have spread widely in Japan. There are many large and small English conversation schools which specialize in classes for children. Disney promotes products that start children as young as infants learning English, and there are many videos and CDs at stores like Toys “R” Us which claim they will help children learn English.

Many linguists believe there is a Critical Period during which a child’s brain is ready to learn a language, and if a language is learned outside this period, the learning will be less successful. However, children learn language in an unconscious, automatic way, and this can only happen if the child is exposed to very large amounts of the language. Also, Children cannot learn a language simply by watching TV or hearing English tapes, nor do they learn very well by being taught grammatical rules. Adults, on the other hand, who are cognitively advanced, can learn well this way. Very often adults progress more rapidly in a second language when compared to children hearing that language in a natural setting (such as my son, going to a Japanese preschool), because they can consciously think about the rules of the language.

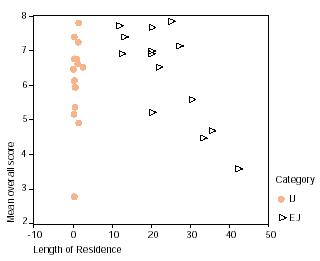

While adults may progress more rapidly than children initially, they then hit a plateau and cannot advance beyond a certain stage, while the children might start more slowly but will keep progressing. This fact can be dramatically illustrated by a research project which I conducted with Japanese people living in the United States. I looked at two groups of Japanese-those who had lived in the US for an average of 1 year and 20 years. They read a story and list of words beginning with the English R or L sound.

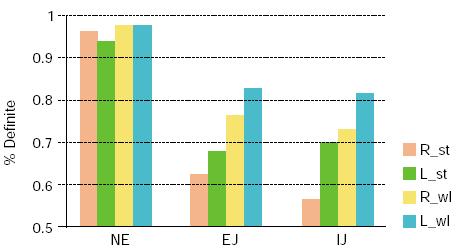

Later, these words were judged by native speakers of English who said whether they had heard an R or an L. One might think that living in a country for 20 years could help improve how well these people could say an R or L sound. However, I found no difference between the two groups in their accuracy (see Figures A and B).

All of the previous research indicates that a child must hear a lot of a second language, from someone he or she likes, in order to learn a language like a native speaker. This is why conversation schools, with only an hour or two of practice a week, do not seem to offer a good way to give children an advantage with English. This, at least, is the opinion of linguists who study second language acquisition and bilingualism.

Because there is such a proliferation of English learning opportunities in Japan, however, I have decided to test the hypothesis that such early experience will not give students any kind of advantage over their peers in the future. In the research project I am carrying out currently, I am testing the abilities of a large number of Japanese students in both grammar and phonology (the sound system) of English. I will be testing their innate language learning ability in order to control for any differences in individual aptitude, and then I will see whether early experience is correlated with any kind of significant advantage in either grammar or phonology.

Until my research is finished, however, my suggestion is that if you would like your child to have an advantage in learning English, don’t just send him or her to an English conversation school, but also set aside one hour a night to interact in English, read English story books, play games in English, sing songs in English, and generally expose your child to English in a way that’s enjoyable. Even if you make mistakes, if your child has enough input from authentic sources of English, your mistakes won’t affect your child’s acquisition of the language.

|

| Figure A: Scores by group on production of R/L words in two conditions (NE=native speakers, EJ=Japanese who had lived 12 years or more in the US, and IJ=Japanese who had lived 3 years or less in the US; R_st=accuracy of R in the story reading condition, R_wl=accuracy of R in the word list reading condition) |

|

| Figure B: Plot of individual scores for the Japanese groups on their R/L production |

|

|

Dr. Jenifer Larson-Hall Completed her degree in Second Language Acquisition from the University of Pittsburgh in 2001. She taught at Kanda Gaigo Daigaku in Tokyo from 1998-1999. She has been at Kyushu University since October, 2001. Her specialties include Phonology and Bilingualism. |