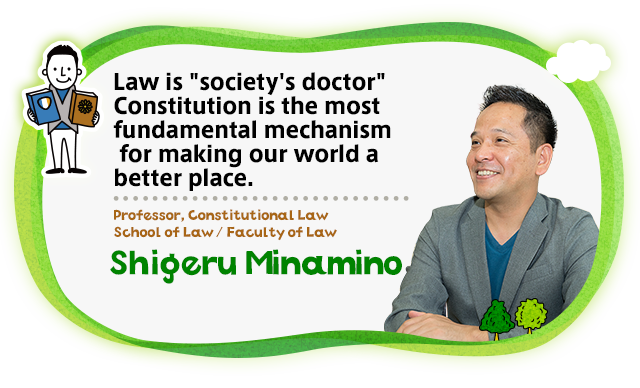

Prof. Minamino talked frankly in a way that was easy to understand, quite unlike law's stuffy, dry image. His father is a film director while his older sister is a novelist.

Prof. Minamino talked frankly in a way that was easy to understand, quite unlike law's stuffy, dry image. His father is a film director while his older sister is a novelist.

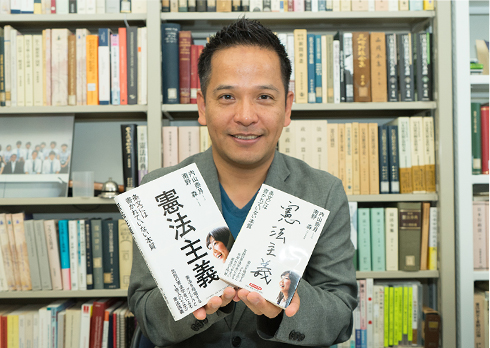

Prof. Minamino is a prolific writer due to his desire to help a wide range of people understand the Constitution. He writes in a wide range of genres, from introductory books that even children can understand to specialist academic texts.

Prof. Minamino is a prolific writer due to his desire to help a wide range of people understand the Constitution. He writes in a wide range of genres, from introductory books that even children can understand to specialist academic texts.

Every year, he takes the students in his seminar group on a five-day field trip to Tokyo to participate in debates with students from other universities. Featuring opportunities to interact with students from other universities and also visit the Supreme Court and various companies, this event is very popular with his students. In this photograph, Prof. Minamino is seen with then Supreme Court Justice Ryuko Sakurai.

Every year, he takes the students in his seminar group on a five-day field trip to Tokyo to participate in debates with students from other universities. Featuring opportunities to interact with students from other universities and also visit the Supreme Court and various companies, this event is very popular with his students. In this photograph, Prof. Minamino is seen with then Supreme Court Justice Ryuko Sakurai.

Prof. Minamino talked frankly in a way that was easy to understand, quite unlike law's stuffy, dry image. His father is a film director while his older sister is a novelist.

Prof. Minamino talked frankly in a way that was easy to understand, quite unlike law's stuffy, dry image. His father is a film director while his older sister is a novelist.

How does a constitution differ from other laws? To put it simply, a constitution is the basic law that sets out the overall nature of a country and its politics. Unlike the Civil Code and Penal Code, which stipulate the rights and obligations of the people, the Constitution focuses on the power of the state: it's a set of rules restricting the temporal power of the state. Today, Japan has almost 2,000 laws that routinely undergo minute amendments. The Constitution of Japan is comprehensive and hasn't been altered even once in the 70 years since it entered into force. By its very nature, the Constitution of Japan has strong elements that make it impossible to rapidly introduce changes (a rigid constitution). If a constitution could be amended easily, those in power would probably do whatever they like. To ensure that this doesn't happen, we constitutional scholars undertake comparative studies of the history and practical effect of constitutions in Japan and other countries, constantly discussing what kind of mechanisms should be created and what proposals should be offered to society in order to help Japan become a better country in 50 or 100 years from now.

Prof. Minamino is a prolific writer due to his desire to help a wide range of people understand the Constitution. He writes in a wide range of genres, from introductory books that even children can understand to specialist academic texts.

Prof. Minamino is a prolific writer due to his desire to help a wide range of people understand the Constitution. He writes in a wide range of genres, from introductory books that even children can understand to specialist academic texts.

One of my areas of research is fundamental theory of constitutional law which focuses on French constitutional law and philosophy of law. My research involves looking at the ideas and history behind constitutions, reading a lot of literature and thinking about such fundamental questions as "Why is a constitution necessary?," "What is a constitution in the first place?," and "What is constitutionalism?" The goal of constitutionalism to constrain the power of the state by means of a constitution isn't easy to achieve. After all, you're up against the power of the state and the fact is that it's easy to ignore the arguments of an academic. You could liken it to a battle between an enormous lion and a single ant.

Every year, he takes the students in his seminar group on a five-day field trip to Tokyo to participate in debates with students from other universities. Featuring opportunities to interact with students from other universities and also visit the Supreme Court and various companies, this event is very popular with his students. In this photograph, Prof. Minamino is seen with then Supreme Court Justice Ryuko Sakurai.

Every year, he takes the students in his seminar group on a five-day field trip to Tokyo to participate in debates with students from other universities. Featuring opportunities to interact with students from other universities and also visit the Supreme Court and various companies, this event is very popular with his students. In this photograph, Prof. Minamino is seen with then Supreme Court Justice Ryuko Sakurai.

For example, in June 2017, Japan's four opposition parties demanded that an extraordinary session of the Diet be held in accordance with Article 53(*) of the Constitution of Japan. However, it was actually held at the end of September. After the calls to convene had been ignored for three months, it was finally convened, but the House of Representatives was dissolved almost immediately, after just 100 seconds, without a policy speech by the Prime Minister or any kind of debate. This is clearly in violation of the Constitution, as you can't say that a session of the Diet was actually convened. However, there are no penalties whatsoever when it comes to the Constitution. A constitution is the supreme legal code setting out the basic order of the state. If the people in power obey the constitution, there's no problem; but if they don't, there's actually nothing ordinary people can do. There are real-life examples of this in various other countries.

So right now, I'm researching the effectiveness of the Constitution. Is it acceptable to overlook the power of the state when the Constitution is violated? Does the system of constitutional review by the Supreme Court have democratic legitimacy? Might not it be the case that the last bastion isn't the Supreme Court but is, in fact, we the people? The amendment of the Constitution is climbing up the political agenda right now, so I think that not only constitutional scholars, but also each and every citizen of Japan needs to think seriously about the Constitution — now more than ever. To achieve this, I believe that it's vital for constitutional scholars to explain the Constitution to all levels of society in a way that's easy to understand.

*Article 53 of the Constitution of Japan states, "The Cabinet may determine to convoke extraordinary sessions of the Diet. When a quarter or more of the total members of either House makes the demand, the Cabinet must determine on such convocation."

The biggest attraction for me is the fact that my field is directly relevant to society. Although my research into principles and theory doesn't itself have a great direct impact on society, it's a very profound field because it involves reading between the lines of the text of the Constitution to identify its essence and then considering that in the context of history and philosophy. This research provides a base, which I think enables me to adopt different perspectives and interpretations from other constitutional scholars when considering rulings and legal provisions or even real-life politics, and then offer my suggestions to society. The whole point of law is to make society a better place, so you might say that legal scholars are the doctors of society. A constitution focuses on "society writ large," in the form of the shape of a nation and its politics. What I find really rewarding is telling people about my ideas for creating a better society — in however small a way — in my own way, based on my own research.

Once the world is at peace, everyone is happy, and we live in a society in which debate about amending the Constitution no longer raises its head, I'll probably immerse myself in the study of French constitutional law and legal philosophy. However, one of the duties of university academics is to meet the needs of modern society, so I want to do my bit to fulfill my social responsibility in areas that relate to my field of research. Right now, I get the distinct feeling that both the general public and politicians have a particular need for expert knowledge. I'm always delighted when people tell me that they've understood something that they didn't previously understand or realized the importance of the Constitution as a result of my speeches or appearances in the media. I'm happy that I can serve as a bridge between academic and society.

![]()