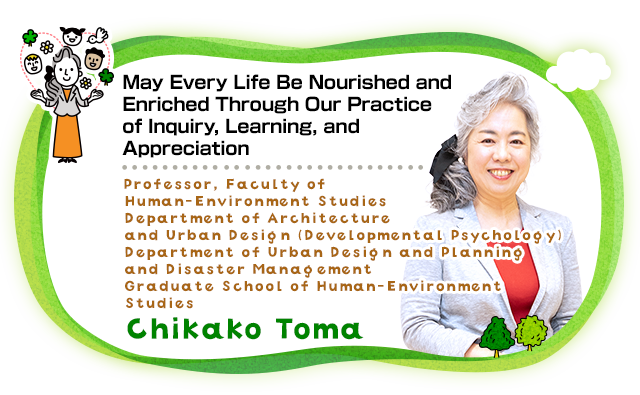

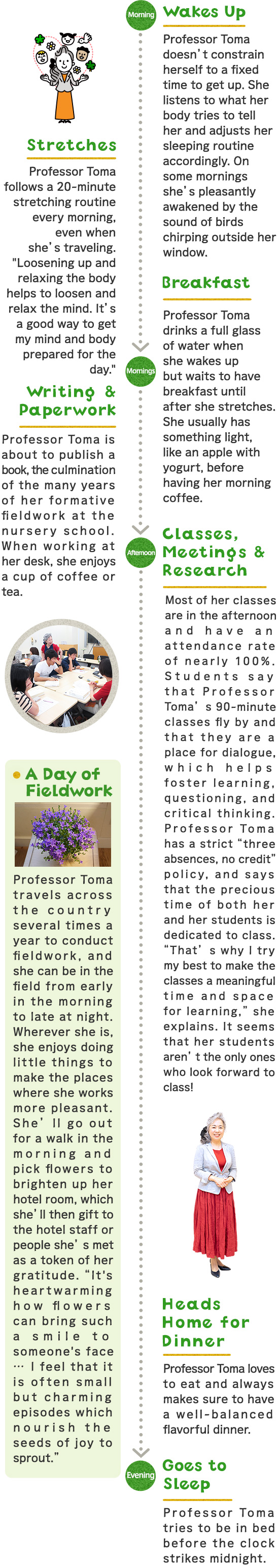

Professor Toma’s responses are thoughtful, and she draws us in with her kind yet intense gaze.

Professor Toma’s responses are thoughtful, and she draws us in with her kind yet intense gaze.

Professor Toma teaches classes for the Department of Urban Design, Planning and Disaster Management and was also involved in the Kashiihama House for All Project, where architecture professors, Japanese students, and international students came together to create a place to congregate in the courtyard of the Kashiihama international student dormitory. She reflects on the experience saying, “It was during this project that I really felt that when we build together, we have an opportunity to grow together.

Professor Toma teaches classes for the Department of Urban Design, Planning and Disaster Management and was also involved in the Kashiihama House for All Project, where architecture professors, Japanese students, and international students came together to create a place to congregate in the courtyard of the Kashiihama international student dormitory. She reflects on the experience saying, “It was during this project that I really felt that when we build together, we have an opportunity to grow together.

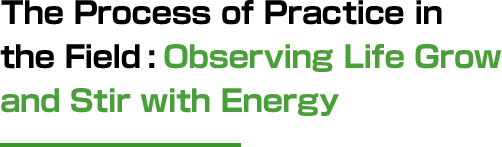

Professor Toma values an interactive class format that encourages deeper learning by positing questions to students and having them engage in discussions that get to the heart of the issue. She also weaves the content of her lectures into her interactions with students, many of whom are shy and hesitant at first but later gain the ability to convey their thoughts in words through this interactive class experience. In order to connect academic discussion with the actuality of experience in real life settings, Professor Toma will even have students hold newborn baby dolls on occasion, saying that most of her students have never held a baby before.

Professor Toma values an interactive class format that encourages deeper learning by positing questions to students and having them engage in discussions that get to the heart of the issue. She also weaves the content of her lectures into her interactions with students, many of whom are shy and hesitant at first but later gain the ability to convey their thoughts in words through this interactive class experience. In order to connect academic discussion with the actuality of experience in real life settings, Professor Toma will even have students hold newborn baby dolls on occasion, saying that most of her students have never held a baby before.

Professor Toma’s responses are thoughtful, and she draws us in with her kind yet intense gaze.

Professor Toma’s responses are thoughtful, and she draws us in with her kind yet intense gaze.

“My field of expertise is developmental psychology, an academic area that asks many questions related to what it means to develop as a human being. What does it mean for a person to grow up and have a fulfilling life? It is neither simple nor easy to give an answer to this question. From birth to death, life is a continuous series of interactions with a variety of different people. Humans have always formed communities of a cultural nature in order to survive, but for a long time, the trend in developmental psychology was to treat the individual person as a unit of analysis for interpreting developmental changes. But I believe that you cannot separate human development from cultural practice, which encompasses any activity that extends beyond the individual, both positive and negative. Even war, for example, can be construed as a cultural practice.

Professor Toma teaches classes for the Department of Urban Design, Planning and Disaster Management and was also involved in the Kashiihama House for All Project, where architecture professors, Japanese students, and international students came together to create a place to congregate in the courtyard of the Kashiihama international student dormitory. She reflects on the experience saying, “It was during this project that I really felt that when we build together, we have an opportunity to grow together.

Professor Toma teaches classes for the Department of Urban Design, Planning and Disaster Management and was also involved in the Kashiihama House for All Project, where architecture professors, Japanese students, and international students came together to create a place to congregate in the courtyard of the Kashiihama international student dormitory. She reflects on the experience saying, “It was during this project that I really felt that when we build together, we have an opportunity to grow together.

Children cannot choose their parents or the circumstances into which they are born. As they grow and live their lives, they inevitably encounter unexpected events. A person can be born into any number of social, cultural, and historical backgrounds, and each has to come to terms with life in their own way. How is such a process of living made possible? What kinds of joy and sorrow does a person experience in life? What difficulties does one face, and what types of support does one receive? What does it mean for a person to lead a fulfilling and enriching life? These are the guiding questions which form the foundation for what I address in my research.

Professor Toma values an interactive class format that encourages deeper learning by positing questions to students and having them engage in discussions that get to the heart of the issue. She also weaves the content of her lectures into her interactions with students, many of whom are shy and hesitant at first but later gain the ability to convey their thoughts in words through this interactive class experience. In order to connect academic discussion with the actuality of experience in real life settings, Professor Toma will even have students hold newborn baby dolls on occasion, saying that most of her students have never held a baby before.

Professor Toma values an interactive class format that encourages deeper learning by positing questions to students and having them engage in discussions that get to the heart of the issue. She also weaves the content of her lectures into her interactions with students, many of whom are shy and hesitant at first but later gain the ability to convey their thoughts in words through this interactive class experience. In order to connect academic discussion with the actuality of experience in real life settings, Professor Toma will even have students hold newborn baby dolls on occasion, saying that most of her students have never held a baby before.

‘Formative fieldwork’ is the practice-based research methodology I have developed in response to these guiding questions. I first proposed the general idea in an article I wrote in 20041. Generally in fieldwork you want to be an external observer, describing events without interfering with what is going on in the field. But in formative fieldwork, the researcher actively engages with people in the field to question existing cultural practices. At a nursery school where I had been carrying out full-fledged formative fieldwork, children were separated by age before the project started. Through this practice-generating project, which adopted the formative fieldwork method, children aged 0–6 all came to share their daily routines and activities with each other. This allowed me to observe the wonderful sight of different relationships developing among the children, between the children and adults, and even among the adults themselves. The older children at the daycare have become much better at noticing when younger children need help and responding appropriately. They are often better at this than many college students I know! The younger children look up to and depend on their big brothers and sisters and do their best to emulate them. The way they eat, play, and clean is fun and voluntary and requires almost no adult instruction or intervention. Even a developmental psychologist such as myself was surprised at the children’s ability to think critically and act for themselves.

This practice-generating method of formative research is not limited to nursery schools but can also be used effectively at welfare-based social childcare institutions and child-raising support centers. It is a virtuous cycle where children and adults grow through generated everyday practices, and everyday practices are nurtured as children and adults grow. Through formative fieldwork, I am able to transcend the dichotomized frameworks of basic and applied research, and I hope this will allow me to continue pursuing the foundational question—that is, how people can nourish each other to grow and live their lives fully and lovingly.”

1 ‘When a Method is Created in Response to a Question - The method of formative fieldwork’ (In Japanese Journal of Clinical Psychology Volume 4, Issue 6)

![]()