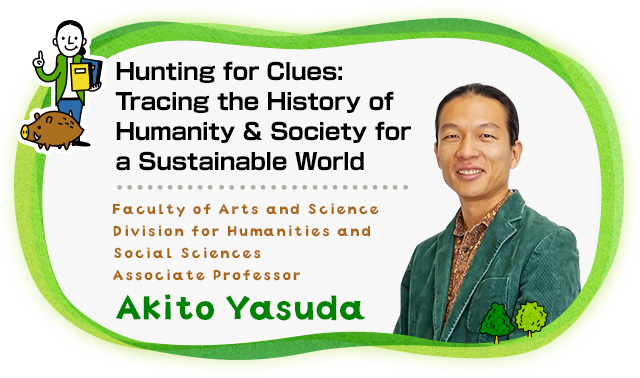

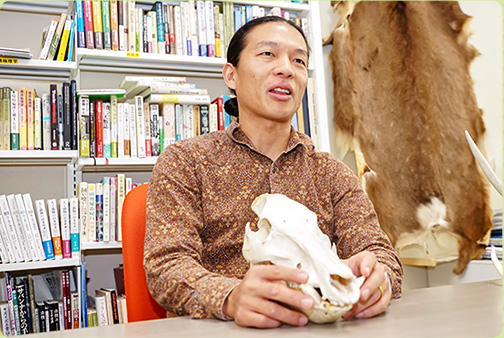

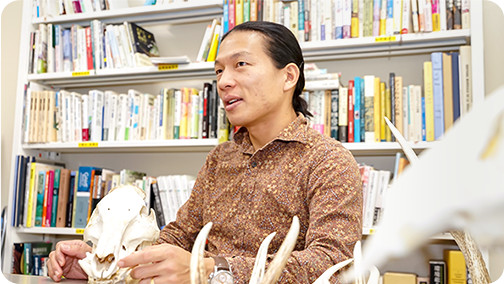

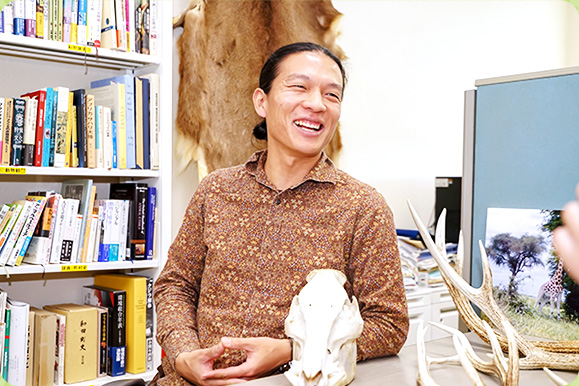

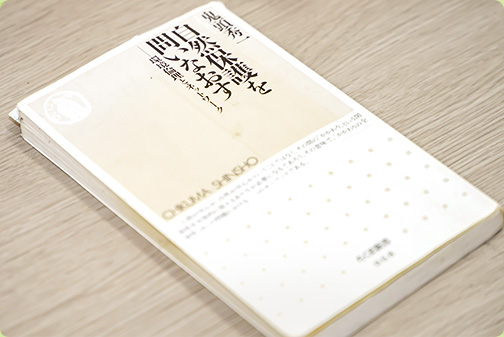

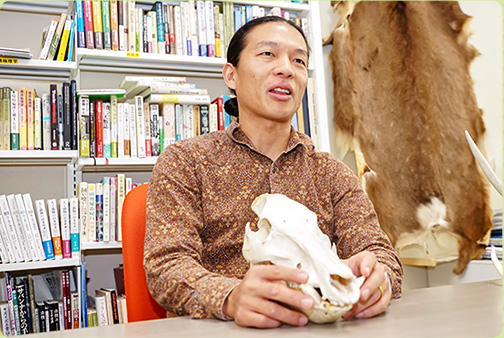

Professor Yasuda has a candid way of speaking. The fur pelt you see behind him is from his first Ezo deer, which he hunted in Hokkaido just after obtaining his hunting license. The skull in the foreground is that of of a boar, hunted right here at Kyushu University on Ito Campus!

Professor Yasuda has a candid way of speaking. The fur pelt you see behind him is from his first Ezo deer, which he hunted in Hokkaido just after obtaining his hunting license. The skull in the foreground is that of of a boar, hunted right here at Kyushu University on Ito Campus!

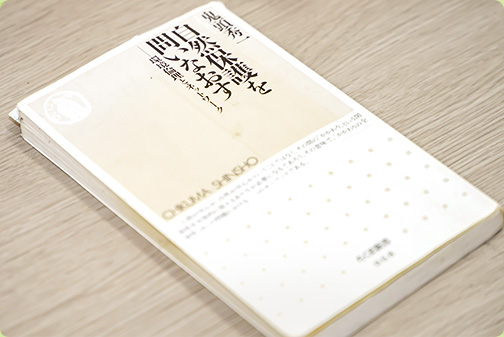

The book Rethinking Nature Conservation, written by Professor Yasuda’s mentor, Professor Shuichi Kito, is foundation of his research. "I’m not exaggerating when I say this book changed my life," he says.

The book Rethinking Nature Conservation, written by Professor Yasuda’s mentor, Professor Shuichi Kito, is foundation of his research. "I’m not exaggerating when I say this book changed my life," he says.

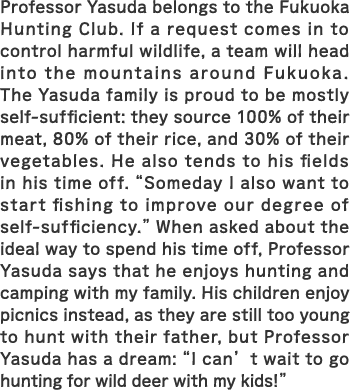

Together with friends in a town where he conducted fieldwork

Together with friends in a town where he conducted fieldwork

Professor Yasuda has a candid way of speaking. The fur pelt you see behind him is from his first Ezo deer, which he hunted in Hokkaido just after obtaining his hunting license. The skull in the foreground is that of of a boar, hunted right here at Kyushu University on Ito Campus!

Professor Yasuda has a candid way of speaking. The fur pelt you see behind him is from his first Ezo deer, which he hunted in Hokkaido just after obtaining his hunting license. The skull in the foreground is that of of a boar, hunted right here at Kyushu University on Ito Campus!

"I've loved animals since I was a kid, and I always entertained the idea of protecting wild animals and the natural environment, which is how I first got into this line of research. But what does it really mean to ‘protect’? If you think about it, you realize that it’s not so simple.

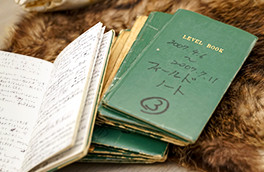

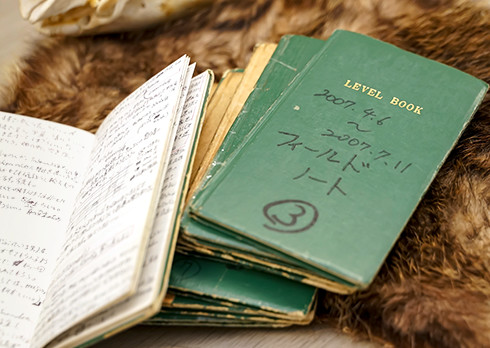

The book Rethinking Nature Conservation, written by Professor Yasuda’s mentor, Professor Shuichi Kito, is foundation of his research. "I’m not exaggerating when I say this book changed my life," he says.

The book Rethinking Nature Conservation, written by Professor Yasuda’s mentor, Professor Shuichi Kito, is foundation of his research. "I’m not exaggerating when I say this book changed my life," he says.

Simply put, my research is the development of symbiotic relationships between people and wild animals, within which I focus on two main themes. The first is considering sustainability in terms of tourism, local communities, and wildlife conservation. In particular, I conduct empirical research based on fieldwork, paying close attention to so-called ‘trophy hunting’ (recreational hunting for horns or furs). In Africa, trophy hunting is said to bring in a considerable amount of tourism revenue and positively affect wild animal conservation and local economies, but can killing really lead to protection? And what negative effects might hunting have on local communities? In my research, I explore these questions and more from the viewpoint of environmental sociology and environmental ethics, looking at ecological and economical sustainability in addition to the local population’s relationship with hunting.

Together with friends in a town where he conducted fieldwork

Together with friends in a town where he conducted fieldwork

The second major theme of my research is about taking life. I’m sure most people think that trophy hunting is cruel because animals should never be killed for fun. But what about the lives of animals that we eat every day?

By educating yourself on the history of hunting, analyzing human psychology, and approaching the issue from different disciplines like folklore and psychology, I think you can find some clues as to how mankind can, and should, coexist with nature and other living beings. I have become a hunter myself in order to fully realize how humans sacrifice the lives of other animals to survive and to explore what this means in practice.

These two themes form the basis of my research as I continue to explore ways for people and wild animals to coexist, through investigation in the field and integrated perspectives from environmental sociology and environmental ethics. In particular, whenever I conduct fieldwork, I am overwhelmed with the amount of information I absorb simply by living in the community. I’ve been to places like Cameroon, Hawaii, and Hokkaido for fieldwork, and those are the experiences that feed directly back into my research—seeing places firsthand, getting a feel for them, and interacting with local people in the community. Needless to say, I don’t plan to stop traveling anytime soon."

When you go out on fieldwork, you feel the differences of the local culture and the environment firsthand, and come to understand how people think and go about their lives. But a single visit does not an expert make. Repeated visits allow you to take the time needed to get to know the people there, sharing food and lodging with them. In my research, I apply this kind of micro view of communities as well as a more broader, macro view of society as a whole. I enjoy visiting different hunting grounds and employing these bug’s-eye and bird’s-eye views.

How long do you think humans were hunter-gatherers over the span of our species’ history? Humans have survived to this day having spent well over 99% of our time on this planet as a species of hunter-gatherers. That’s why humans are equipped with a basic instinct for hunting. One example: it feels good when you toss a crumpled piece of garbage into a trash can across the room, doesn’t it? That’s our hunting instinct at work. It’s the same feeling you get when your spear or arrow pierces your prey.

Thoughts on hunting living creatures vary greatly by era, region, and from person to person. Since long ago, hunting has been a pastime of the elite as a symbol of privilege, and animals were long used to relieve stress in games that we would now consider cruel. Nowadays, many people's desire to protect these cute and cuddly creatures conflicts with their dietary habits. That's what makes this research so interesting. I am able to see the many different aspects of human nature, rather than any one aspect—like hunting, or eating meat—in isolation. By necessity, my research spans fields like anthropology, folklore and history, in addition to environmental sociology and environmental ethics. These fields all have to do with how people live. Nothing intrigues me more than questions that ask us who we are as humans and what we are as society, when considering the coexistence of humans and wild animals.

![]()