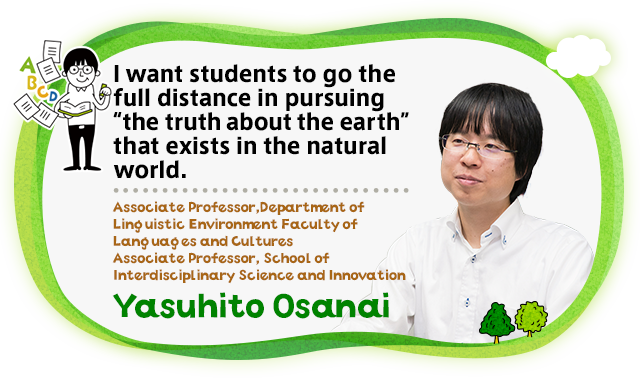

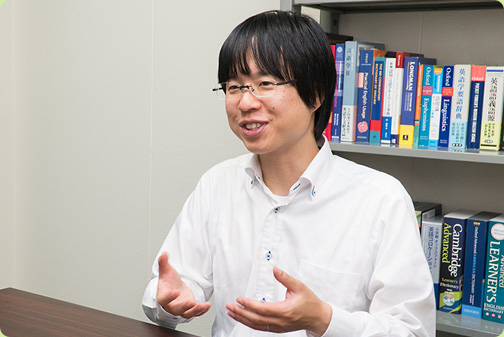

As an energetic young researcher, Dr. Uchida, who chatted good-humoredly with us, takes the initiative in organizing events and partnering with other fields. He is also involved in the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation which will open its doors in 2018

As an energetic young researcher, Dr. Uchida, who chatted good-humoredly with us, takes the initiative in organizing events and partnering with other fields. He is also involved in the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation which will open its doors in 2018

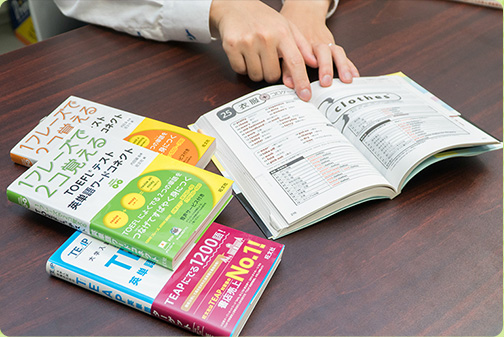

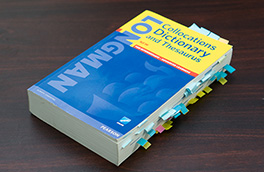

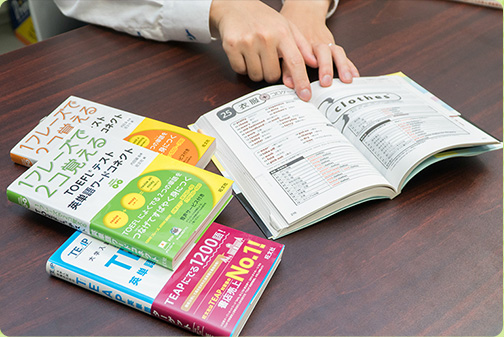

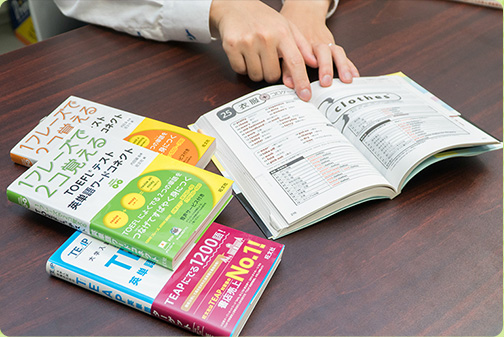

The books in which Dr. Uchida has had a hand are many and varied, spanning everything from general books to dictionaries and materials for teaching English. You might even find the name “Satoru Uchida” on an English book in your collection.

The books in which Dr. Uchida has had a hand are many and varied, spanning everything from general books to dictionaries and materials for teaching English. You might even find the name “Satoru Uchida” on an English book in your collection.

“Rather than trying to learn English as individual words, it’s more efficient to learn it as multi-word phrases and collocations; doing it that way makes speaking English easier, too,” says Dr. Uchida.

“Rather than trying to learn English as individual words, it’s more efficient to learn it as multi-word phrases and collocations; doing it that way makes speaking English easier, too,” says Dr. Uchida.

As an energetic young researcher, Dr. Uchida, who chatted good-humoredly with us, takes the initiative in organizing events and partnering with other fields. He is also involvedin the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation which will open its doors in 2018

As an energetic young researcher, Dr. Uchida, who chatted good-humoredly with us, takes the initiative in organizing events and partnering with other fields. He is also involvedin the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation which will open its doors in 2018

Words are the medium that humans use to communicate. Behind every single word is a whole host of linked knowledge and you can’t truly understand the meaning of a word unless you actually look at the knowledge that underpins it. For example, in the case of the word “buy,” you can’t use it properly as a word without an underlying knowledge of the concepts of business transactions and paying money to receive something. In other words, hearing the word “buy” evokes the knowledge of a business transaction. This approach is called “frame semantics” and is part of the field of cognitive linguistics.

Another major theme in my research is applied linguistics which involves applying linguistics research to the study of the English language. Vocabulary size is closely linked to language acquisition. For example, there’s the word “telephone.” Most Japanese people know the word “phone” in English. But would they be able to produce the expressions “answer the phone,” “hang up the phone,” “use the phone” unprompted in English based on the equivalent expressions in Japanese? In particular, in the Japanese education system, which places great emphasis on studying for university entrance examinations, there is a tendency to memorize individual words in English by associating them with individual words in Japanese. The Japanese expression for “hang up the phone” is “denwa wo kiru,” where “denwa” means phone and “kiru” means cut. As such, Japanese people tend to render the expression wrongly in English as “cut phone.” There are two elements to vocabulary: receptive vocabulary, which is the vocabulary whose meaning you understand when you see it, and productive vocabulary, which is the vocabulary that you yourself can say and write. Most Japanese people have a high level of ability in the area of receptive vocabulary but low ability when it comes to productive vocabulary. Accordingly, to build productive vocabulary capabilities, I’m promoting efforts to introduce knowledge of collocations (the combination of one word with another/others) into today’s classroom.

The books in which Dr. Uchida has had a hand are many and varied, spanning everything from general books to dictionaries and materials for teaching English. You might even find the name “Satoru Uchida” on an English book in your collection.

The books in which Dr. Uchida has had a hand are many and varied, spanning everything from general books to dictionaries and materials for teaching English. You might even find the name “Satoru Uchida” on an English book in your collection.

Hardly any words function as independent units; they generally consist of multiple, idiomatically linked units of vocabulary. That’s why using collocation to learn words as phrases enables people to learn more modes of expression from a single unit of vocabulary. There are three key advantages to using collocation. The first is that it results in more natural English. Secondly, it lays the foundations for the productive skills of speaking and writing in English. Lastly, it provides a deeper understanding of the meanings of words.

“Rather than trying to learn English as individual words, it’s more efficient to learn it as multi-word phrases and collocations; doing it that way makes speaking English easier, too,” says Dr. Uchida.

“Rather than trying to learn English as individual words, it’s more efficient to learn it as multi-word phrases and collocations; doing it that way makes speaking English easier, too,” says Dr. Uchida.

A corpus — a database of words — is very useful in building productive vocabulary through the use of collocation. A corpus is a database compiled for research purposes, containing real-life, real-world examples of the use of words to which specific attributes have been assigned, such as the part of speech or genre that they represent. Corpora (the plural of corpus) can generally be used free of charge and enable the user to investigate the frequency with which one vocabulary unit and another are combined within databases of several hundred million words. If you use corpus to analyze the difference between the words “big” and “large,” you start to see differences emerge in the words immediately following them. Big business, big chance, big difference.... large scale, large number, large population.... Investigating the points in common between the words to which they’re linked, you can see that “big” expresses subjective size, while “large” refers to size in objectively measurable terms.

Going back to the subject of cognitive linguistics, which I mentioned at the outset, let’s look at the example of emotions. Amorphous emotions are often likened to liquid. In Japanese, we talk about anger building up or overflowing (“ikari ga tamaru” and “ ikari ni michiafureru”) and there are similar equivalents in English. However, different expressions may be used in different countries as a metaphor for the container in which the anger = liquid builds up, due to cultural differences. Thus, by seeing a word, we can gain an understanding of how we look at the world and how we perceive the world using words. True meaning is hidden behind words. My goal is to increase Japanese people’s productive vocabulary by enabling them to learn these true meanings effectively.

What I find interesting is being able to use linguistic theories and corpora to objectively dissect the words that we use every day without a second thought. There is always something to be discovered in them. Sometimes, we misunderstand the true meanings of words even though we habitually use them, and these misunderstandings commonly go unchallenged. For example, you can’t instantly explain the difference between “high” and “tall.” In Japanese, both meanings are covered by the word “takai.” Textbooks don’t explain it, so it ends up being something that usually isn’t seen. That’s why you don’t understand the differences unless you analyze them. The opportunity to make discoveries as a result of such analysis is what I find fascinating.

If something isn’t yet in the dictionary, it means that there’s still scope to incorporate new knowledge. Those discoveries are undoubtedly handy and helpful, and I want to tell everybody about them! I’d be really happy if I could do so by putting them in the dictionary. Being able to see my discoveries and intuition through to the outlet of applied research, education is really interesting! Another part of the appeal and the thing that I find rewarding is that feeding back my own research into front-line education gives me the chance to be involved in developing the next generation of leaders.

![]()