The rhythm we hear: sound, neural processing and perception

How does the brain process rhythm and measures of sound that are strung together in a sequence? Research elucidates preceding sound context affects the brain’s perception of time.

Rhythm is vital to our speech and music. However, what we think we hear sometimes differs from the actual rhythm of the sounds. Prof Emi Hasuo studies how we hear and processing of the brain and how the preceding sounds affect what we think we hear.

What are your research areas?

My research interests are rhythm perception and time perception. In our daily life, we use words and music to communicate, and as you know, rhythm is fundamental in music but also speech. In Japanese, the word "neko" means “cat” and with a pause, “nekko” means "root". “Ojisan” means “man” and the longer “ojiisan” means “old man”. There are quite a few words whose meaning changes when the rhythm changes.

With music, if there is no rhythm, there is no music! Rhythm perception is based on the perception of time units of a few hundred milliseconds, which is shorter than a second. Thus, my research subject is the perception of very short time intervals. Many people think that the rhythm played and the rhythm that we perceive is the same. But sometimes, it's a little different.

Please see for yourself. I have two demonstrations, and in each demo, you will hear three beeps. There are two intervals between the three beeps, so listen to see if the two intervals sound the same or different lengths.

First :

Second:

I suppose the first demonstration sounded clearly uneven, while the second one sounded more even. When we look at the physical (actual) durations of the time intervals, in the first demo, the first time interval was 60 ms longer than the second interval, so it was physically uneven. This probably matches what you perceived. In the second demo, the sounds of the first demo were simply flipped. So, physically, the second demo was also uneven, with the second time interval being 60 ms longer than the first interval. Curiously, in the second demo, the physically uneven rhythm sounds evenly spaced. In other words, physical rhythm may be slightly different from the rhythm we hear. This can be demonstrated in such cases.

The duration of the two neighboring time intervals are similar, so you may feel that is why you don’t hear their difference, but that's not all. If that's all it is, the first demo should sound equally spaced too. It is a feature of our perception that they sound evenly spaced, even though they are not really evenly spaced. The reason why the actual rhythm and the rhythm that we hear may be different is because our brains process temporal information in such a way. Perhaps the brain does this when processing the rhythm of words and music. I am conducting research using psychological and neurophysiological methods to find out.

Demonstration made by Emi Hasuo consulting the book:

Auditory Grammar. (2014) Nakajima, Sasaki, Ueda, Remijn. Corona Publishing.

(https://www.coronasha.co.jp/np/isbn/9784339013283/)

What made you interested in this subject?

I didn't intend to study rhythm. I first became interested in research when I was a child. My father, who is a medical doctor and researcher had a big influence on me. Ever since I was little, he would point out things around me, like animals and show me how to observe their traits. So, you could say I grew up in an environment where it was not unusual to become interested in nature and living things and be curious about how it all worked.

I did not initially plan my schooling to become a researcher. I first attended high school and university to learn music performance. I specialized in piano. I practiced the piano every day and took many lessons. Through such experiences, I noticed that the same performance is heard differently by different people. For example, my piano teachers can hear very small differences. They notice some very precise details.

Even things that I could not hear when I was playing. I thought it was amazing. I think they have a very well-trained ear. I became interested in human hearing because I thought that the way people hear sounds can be completely different.

I attended Kyushu University for five years for my master's and doctoral courses. I specialized in auditory psychology. One of the research themes that my supervisor had at the time was rhythm perception. That's how I encountered rhythm perception.

This research on rhythm perception and time perception is very structured and defined. The stimulus is rather simple and it fits well with the classic experimental method in experimental psychology. The data that is obtained is straight-forward and very beautiful. I enjoy it a lot, and I've been continuing my research ever since.

How do you conduct your research?

We conduct experiments where participants are asked to listen to sounds and give answers about the sounds. I conduct these experiments in the laboratory. In the beginning, my research involved physically simple sounds. These sounds were good for basic research, but they are sounds we encounter only in laboratories, not in our daily life. So, as my research went on, I started using a little more complex sounds, and tried to see how far the findings in basic laboratory studies can be applied to our perception in daily life.

I do this step by step.

Recently, I have become interested in researching differences between individuals. In my experiments, I use very simple sounds, but it seems that even such simple sounds are perceived differently by different people. I wonder what creates those differences.

I think it may be due to previous hearing experiences, such as language, music training, and other things. I hope that research from such findings can lead to application in music and language education.

How are neuroscience and perception important in understanding sound and music?

Both music and words are sounds that people make, and they are used for communication. Sound itself is important to establish communication, but if there is no one to receive it, communication cannot exist. So, how the sound is heard by people who receive it is a very important issue, and that is what neuroscience and perception studies look at.

How do your recent publications add to our understanding of this phenomenon?

What we found in my 2020 paper, Certain non-isochronous sound trains are perceived as more isochronous when they start on beat, is that even if the rhythm is physically the same, it can sound different.

Specifically, we made a rhythm pattern that is physically a little uneven, and added some preceding sounds that induce a feeling of beat before this rhythm pattern. What we found was that this rhythm pattern sometimes sounds close to even while it sometimes sounds clearly uneven, depending on the beat. In other words, the preceding sounds made the physically identical rhythm sound completely different. We found this phenomenon for the first time with this study. I think it exists in real music as well. This is interesting, and I am also excited to investigate what is happening in the brain.

Actually, this phenomenon can be a quite useful tool to investigate brain activity related to rhythm perception. In a normal neuroscientific experiment on rhythm perception, we record brain activity while the participant listens to some rhythm pattern. In this case, the recorded brain activity will include both the activity related to processing of the physical properties of the sounds and the brain activity related to rhythm perception. It is very difficult to tell whether the activity you are currently seeing really reflects rhythm perception or whether it reflects some other processing of sounds themselves.

With our phenomenon, however, we can change the perceived rhythm while keeping the physical rhythm pattern the same. This makes it possible for us to capture the brain activity related to rhythm perception apart from the activities related to the physical properties of the sounds. This could be a breakthrough for neuroscience research on rhythm perception.

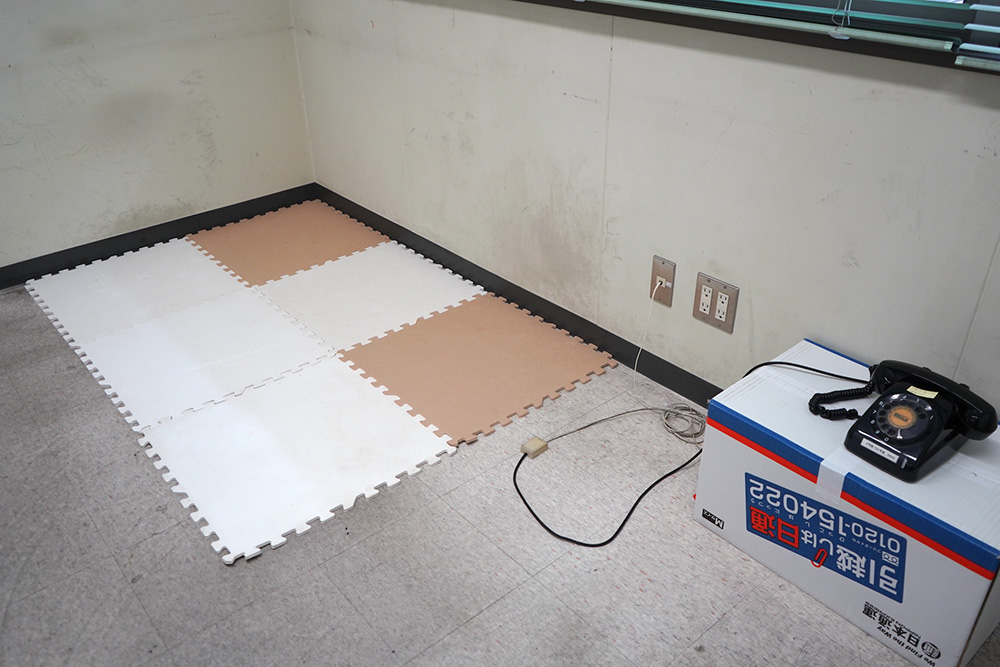

I began my position this April, so I am planning my research here at Kyushu University now. There are two more professors of auditory psychology in the same building, and they have some soundproof rooms. I will share use of the soundproof rooms with them. For brain research, I will use a booth in another building.

You completed your postdoctoral (medical) and part-time (design) studies at Kyushu University and a psychology postdoctoral fellow at Laval University in Canada. Is the research environment at Canadian universities different from that in Japan?

Having worked as a postdoc for a long time, I find postdoc life is the same no matter where I am. I was happy to discover that wherever you are, you plan the experiments yourself, you analyze the findings and publish the results. It is the same everywhere.

As for the language issue, Laval University is in Quebec province, which is in the French speaking part of the country. I can't speak French at all, so I was grateful that the students and everyone in the lab enjoyed speaking in English. There were slight language barriers in everyday life but it was a great experience.

Later, I observed a difference in culture. For example, when conducting experiments in Japan, subjects usually arrive on time. There are times when people are a few minutes late, but in Canada, there were subjects who were boldly late, sometimes even two hours late but somehow it still works. The laxness and freedom were nice. It was fun. I think the most important experience of my life in Quebec was that I was able to make friends with many people of different nationalities, ages, professions, and fields of expertise that I would never have met if I had been studying in Japan. I am still in contact with some of them, and my life in Canada was blessed with truly kind people.

I heard that you have a young child. How do you balance parental responsibilities with work?

I'm not confident that I am managing both well, but I personally believe that my job is only possible if my child is growing up in a healthy manner. It takes a lot of work, and I must prioritize my child.

In my previous positions, I worked under a discretionary flextime contract, so I was able to pick up my child from daycare early. Now I have classes in the evening, so I ask my husband to watch and care for our child and I go back to work. When I participated in the spring guidance, I brought my child to work. I feel blessed and grateful to be able to do so.

I am very grateful that my husband’s workplace allows for flexibility in work conditions. When my child grows up, I would like to repay the favor to my coworkers by putting more weight on my work. Looking around me, it seems very difficult for professors to raise (their own) children. I hope to show my students that it is possible.

Support is very necessary.

Definitely. I really wish we could get the cooperation of society because we can't do it on our own. My family just moved here, so we are now in the process of creating a routine for my child. My son is getting accustomed to the new school here. I will spend more time at work in the office, but as of now, I am caring for my child without help nor after school activities.

I hear that there are students who do not go on to get their PhDs because postdocs work circumstances are not good. How did you overcome the challenges before getting this job?

I think it's a very serious problem. I don't feel like I've overcome the issue at all. I was lucky enough to eventually find this job, and there were so many things that happened before then. I got married eight years ago, and at that time my husband was also still a fixed-term researcher. Basically, I followed my husband, so when his work changed, I looked for new work to be with him. It is important that we live together.

So, the meaning of fixed-termed contract employment, of course, is that it's a short contract, so we have to constantly look for the next job. We don't know when or where the next job would be advertised, so we were always applying. I didn't know where I will be next year either. If I find something that seemed like I can apply to, I did so, but I wasn’t sure if I would be able to accept the offer because I didn’t know where I will live to be with my husband.

I had such a difficult time finding jobs. Even if I received an offer for a part-time job, I explained the situation, and some places were so kind and they allowed me to have the option of canceling at the last minute. Sometimes I had to turn them down because I wouldn’t live there. It wasn’t easy to find jobs.

When I gave birth, I was an unpaid researcher and I didn’t have maternity leave. I couldn't go to work and leave my child in care, so I frequently stayed home writing while caring for my child.

Luckily, after that, I got accepted as a RPD researcher at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a program to support researchers returning to work after childbirth. Unfortunately, this was also for a fixed term, and during the pandemic I had to suspend my research. I didn't get paid for two years, but I was able to retain the position during the pandemic. When that was coming to an end, I found a job posting for an assistant professor position here at Kyushu University, and thought it was my last chance. I was extremely lucky to have found this position. At the time we were living in Hiroshima. My husband had a job in Hiroshima, so I thought it would inconvenience many people, but I applied because I thought it was my last chance.

If I didn’t get this position, I thought I would have to pursue a different path. It is really, really hard. The post-doc situation is a difficult issue and there are many people suffering. I was blessed with kind professors and colleagues that supported me. I was able to continue research as a post-doc, but I know there are lots of others who are not as fortunate. I think it's a social problem, not an individual researcher's problem or responsibility.

Research that produces results right away gets a lot of attention, but there are lots of important research that isn’t flashy or glamorous. Research that seems dull at first glance is important too. I really want to live in a world where society is supportive in that way. Talking about this issue, I see the faces of researchers I know who are really suffering. Many of my friends and colleagues, in my mind. I want the values and support system of the world to change.

My husband's workplace is understanding, and allows working from home, so even after the pandemic, the company continued to implement ways to improve working conditions. Now he goes to the office in Hiroshima once or twice a week as needed. Thanks to that, we can live together as a family. If I hadn't been able to get this job now, I think I would have had to give up on the path of being a researcher and reconsider other options.

How will your research contribute to Vision 2030?

Vision 2030 aims to solve social problems by connecting different research fields called integrative knowledge. My research is about connecting music as an art with empirical science such as psychology and neuroscience. Through my research, I hope to deepen our understanding of human beings themselves. In the future, by advancing the analysis of individual differences, we will propose and support sound environments that suit everyone. I would like to contribute to the development and realization of a sustainable society through such efforts.

More information on Prof Hasuo can be found on her website.

A link to Prof Hasuo’s paper discussed in the article: Hasuo, E., & Arao, H. (2020). Certain non-isochronous sound trains are perceived as more isochronous when they start on beat, Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(4), 1548–1557. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-019-01959-2.