Investigating the relay of life

with Prof. Katsuhiko Hayashi

As science and technology advances, what were once archetypes of science fiction are slowly materializing into reality, and perhaps the hottest topic is ‘regenerative medicine’ and its representative body, the stem cell. But while research on stem cells has been happening since the 1960s, their application in medicine is still in its infancy.

One of the many reasons for this is the complex inner workings of our cells. From the cells in your eyes that register light to the ones in your skin that make your hair grow, our entire body is made up of cells, all having distinct functions grouped into categories, or ‘cell types.’ Humans have close to 200 different cell types depending on the stage of development.

All these cells come essentially from a single fertilized egg cell that grows, divides, and changes to form the organism. A ‘stem cell’ is—in the broadest sense of the term—a cell that has not ‘differentiated’ or committed to become a specific cell type. Researchers can make entire careers trying to understand the intricacies of how stem cells differentiate. In this complex realm, Katsuhiko Hayashi, professor of Kyushu University’s Faculty of Medical Sciences, sets his eyes on the most unique cell type of them all: germ cells.

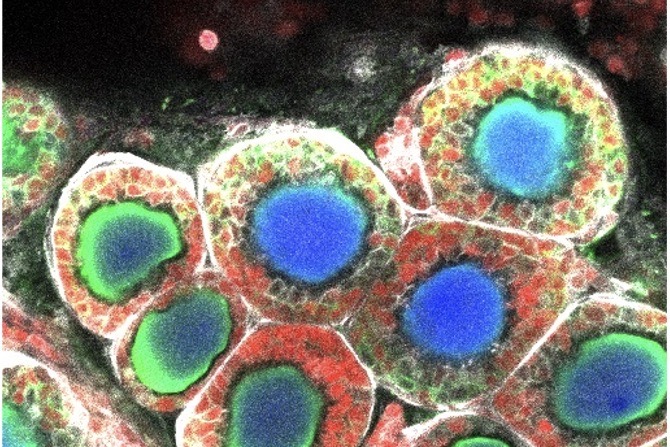

“Broadly, biological cells can be placed into two major categories, somatic cells and germ cells,” explains Hayashi. “Germ cells are cells that generate gametes, or sex cells, such as sperm or eggs. Somatic cells are everything else. Germ cells are incredibly unique. They can divide via mitosis and meiosis and are the only cells that can transfer genetic information and create new life.”

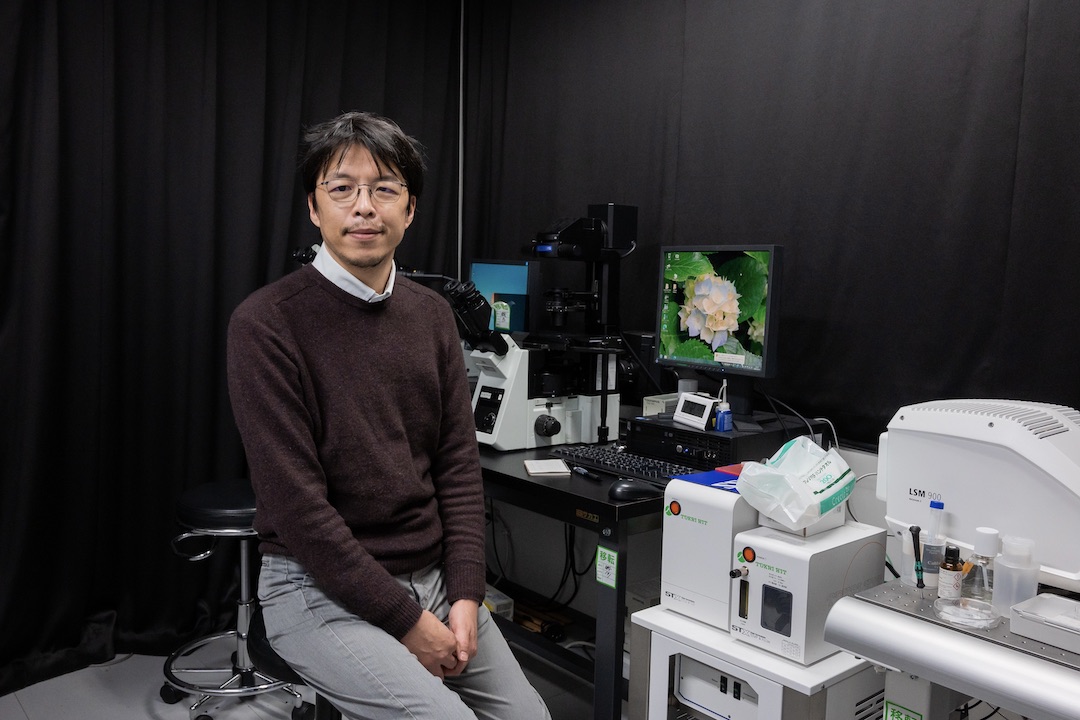

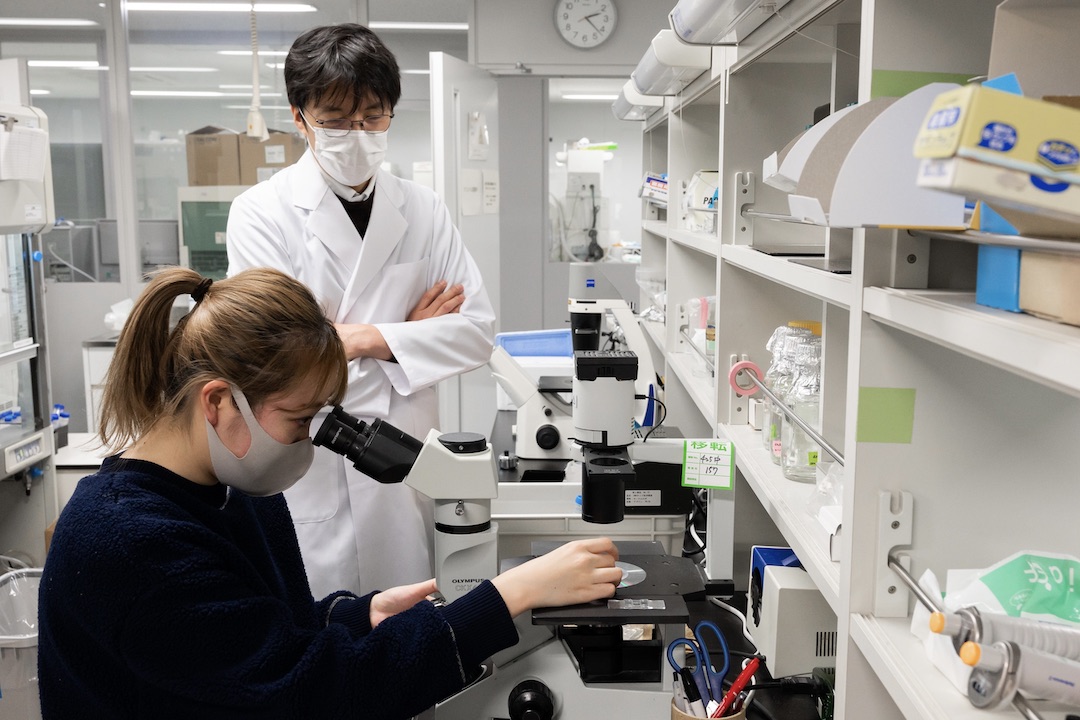

Hayashi’s work focuses on the fundamental mechanisms of gametogenesis, or how gametes form in the body. Like any other cell, gametes undergo precisely controlled steps to become viable. By meticulously looking at each step closely in both mouse and human cells, researchers are slowly chipping away at these mysterious processes.

“The ‘primordial germ cell’ is the fundamental precursor to all gametes, and that’s where we start looking,” Hayashi states. “Over the years, we’ve revealed key molecules and conditions for each step in its differentiation, and we started recreating the same conditions in the petri dish to get a closer look.”

In recent years, Hayashi’s team has been able to replicate the conditions for developing oocytes—egg cells—from embryonic stem cells (ES) and even induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS). They have even gone so far as to recreate both the cells that make the oocyte and the cells that act as the support system for that oocyte, essentially making it possible to produce mature oocytes in their entirety in laboratory conditions.

In this world where gametes can be produced from stem cells in the lab, the next question, naturally, is its application in humans. Hayashi admits that his research has such potential but cautions against being hasty.

He explains, “We are only beginning to scratch the surface of this field, with still many questions we must answer and clarify to even begin looking towards human application. Now is the perfect time to discuss the ethics of the future of this research.”

As this all moves forward, Hayashi continues to work hard unlocking the fundamental mechanisms that brings about life.

“Much like life where we pass down our genes, we pass down knowledge to the future though scientific research,” concludes Hayashi. “As I add new knowledge to our field, I have a responsibility to be part of this eternal relay and pass on the work to the next generation of talented young researchers.”