Engaging society with art as a means for recovery

with Prof. Mikako Tomotari

Standing in a garden, a wood pavilion shades visitors enjoying a view that changes with each season and year. In the entrance of an elementary school, a sculpture of a dragon—powerful yet kind—welcomes children starting a new school day. A statue of a praying goddess in a train station tucked away among the mountains watches over travelers departing on a new journey.

Now symbols for healing, inspiration, and remembrance, all of these objects began as the remnants of a disaster that disrupted people’s lives and caused pain and hardship. Leading the effort to transform their meaning is Mikako Tomotari, a professor of Kyushu University’s Faculty of Design specializing in sculpting with wood and iron.

“Through art, we have opportunities to create unique solutions for addressing and resolving societal problems arising from cultural disruption, social alienation, and anxiety resulting from disasters,” says Tomotari.

The target of many of her recent works has been the destruction and grief caused by torrential rainfall in northern Kyushu in July 2017, which resulted in the displacement of an estimated ten million metric tons of mud and 200,000 metric tons of driftwood.

The wooden pavilion—constructed without using a single nail or screw—was created from trees damaged during the disaster. Tomotari chiseled both the dragon and goddess by hand, the former beginning as a piece of driftwood and the latter as a beloved cherry tree that stood for over 300 years before falling during the rains.

Through the interactions that this socially engaged art stimulates in local communities, Tomotari aims to overcome negative feelings produced by the disasters while at the same time remembering the past.

“Art gives form to emotions, society, life, and other abstract concepts, thereby helping people to come to terms and begin to look forward again,” Tomotari explains. “With my research, I am exploring how sculpture can give hope and love shape to communicate visually what cannot be communicated with words and improve people’s lives.”

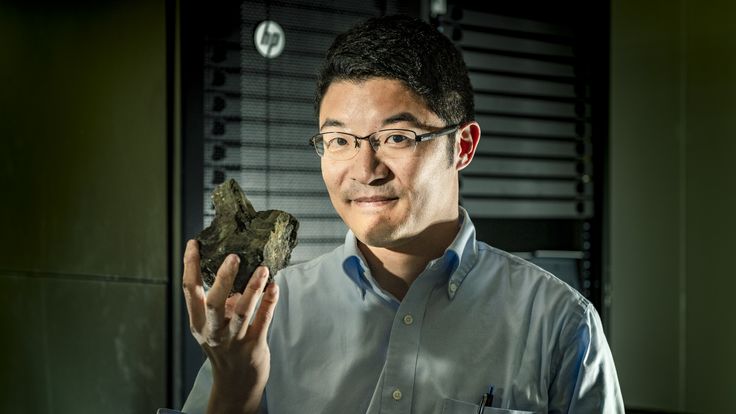

Another focus of her efforts applying art to support society has been the study and reproduction of four pieces for use by practitioners of Shugendo on Mount Hiko, which sits on the eastern boarder of Fukuoka Prefecture.

Founded over 1,000 year ago, Shugendo focuses on enlightenment through self-denial and training in the mountains. A ban starting in 1872 because of its mixing of Shinto and Buddhism led to the damage of many religious articles both intentionally and through neglect, but Shugendo has since been revived.

To re-create the religious objects for Mount Hiko—one of Japan’s three major mountains for Shugendo—Tomotari turned to 3D scanning technologies to analyze their structures while limiting contact with the originals. Studying cultural records to help understand what the missing parts would look like, she then employed traditional materials and techniques to fabricate the reproductions.

Tomotari’s ties to the project run deep, as her ancestors were Shugendo monks who lived on the mountain. These ties are also part of what started Tomotari on this journey in the first place.

“Seeing a single pine tree by my ancestor’s grave made me aware of this cycle of returning to the earth and bringing new life to that tree and the environment. It was as if receiving a message from the past,” recalls Tomotari.

“In the same way, I want to develop art that can make visible the invisible and invoke these kinds of connections and messages for others in the future.”

For this, Tomotari and her students are also looking to create new forms of expression through unique combinations of engineering and art, such as mixing Zen and media art or augmented reality and performance. In her pursuit of art that can engage and support society, she keeps her mind open to any chance meeting that could inspire her next.