Unlocking the hidden potential of plants

Discover the Research: Article 5 – Akiko Maruyama, Faculty of Agriculture

Plants produce organic compounds from surrounding inorganic matter, and in turn, animals—including humans—live off the organic matter that these plants create. We spoke to Professor Akiko Maruyama from the Faculty of Agriculture to learn more about the essential nutrients required by plants, which support life on Earth, and her fascination with plant science research.

*The original Japanese version of the interview can be found here

A plant’s way of life

Could you tell us about your current research?

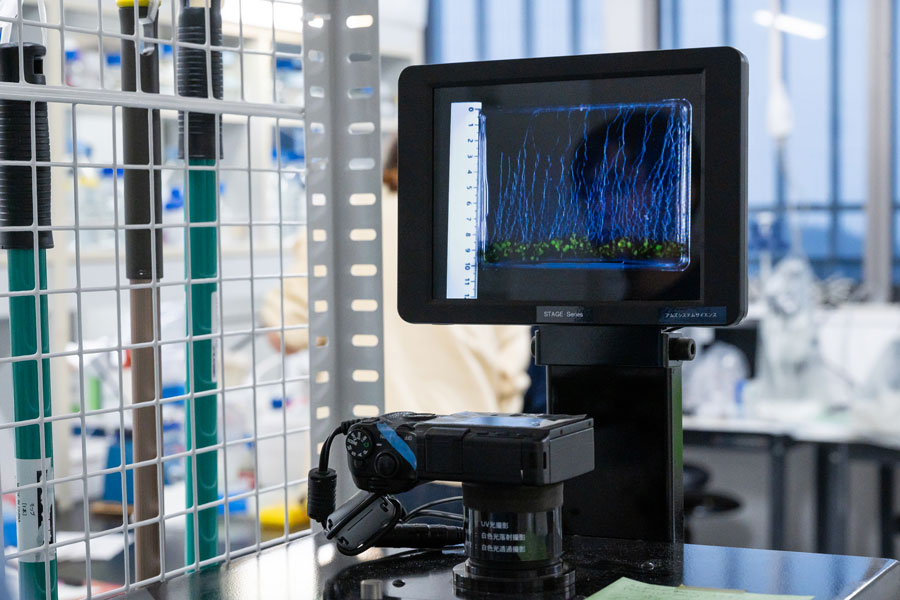

I specialize in plant nutrition research. Plants absorb inorganic matter to produce organic compounds. Take photosynthesis, for example. Using carbon dioxide and water, with the help of sunlight, plants can create organic compounds—molecules containing carbon atoms—which provide us with essential calories when eaten. By itself, carbon dioxide is toxic to humans, but it can be turned into something useful to us with the aid of plants. In addition to carbon dioxide and water, plants also take in nutrients, like inorganic ions. I'm studying how plants convert these inorganic ions into organic matter and how this process of assimilation is regulated.

You’re also studying the effects of environmental stress on plants, is that right?

Yes, we are investigating how sulfur-containing compounds work inside plants subject to environmental stresses. Sulfur is characterized by its high reactivity. It regulates a plant’s metabolic reactions, promotes its antimicrobial activities, and protects it from environmental stress. So, I’m working with the idea that if we improve the capacity of plants to uptake sulfur, we can create plants with a higher tolerance to environmental stresses.

Discovering a sense of wonder and passion in plants

How did you become interested in the study of plants?

I have been interested in biology since childhood. And I loved to eat. I thought that if you combine biology and food, you get plants (laughs). But I didn't really know that I wanted to study plants when I started university. After considering what I wanted to do in the future, I entered the Department of Biology in the Faculty of Science at Tohoku University with a vague interest in living organisms. As a high school student, I had no idea what a person would study in the Faculty of Science. But I knew it seemed like fun, like a space to explore the unknown, and I embraced the urge to plunge into this new and fascinating world.

What made you want to become a researcher after entering university?

As a student, I never thought that I could become a researcher. I was initially doing research for my thesis, and as I considered possible career paths, I decided that I ought to do something that I loved. That's why I opted to be a researcher. But, as a graduate student, it wasn't as if I was studying plant nutrition as I am now.

So, how did you get into plant nutrition?

Initially, I was studying germination in the lab, but in researching how cyanide promotes germination, I began studying plant metabolism. After that, I went on to examine the enzymes that detoxify cyanide in plants. Luckily, we were able to discover the main structure of the enzyme, but a question remained regarding the significance of these enzymes and cyanide metabolism for the plant's existence. Then, I figured I wanted to focus on the essential elements for plant growth, which would allow me to analyze the role of proteins directly, so I shifted my field of research to plant nutrition using model plants.

Fascinated by the treasure hunt of research

What do you consider the appeal of research?

The greatest allure of research is the fact that you might be the first person in history to discover something previously unknown. I think all researchers, regardless of their field, feel this way. For example, when we can't identify the protein causing a certain reaction, we need to extract the protein or gene from the plant that causes that reaction to determine its identity. When you get that protein sequence, it is one of those "aha" moments.

Right, making the first discovery is wholly unique to researchers.

In plant research, we often know what causes a reaction and what it produces, but the process itself remains a black box. At times like these, I look for agents that control similar responses or, alternatively, select variants that can stop a reaction in an effort to identify what factors play a role in achieving a desired outcome. Conversely, we also investigate what happens to a plant when it loses a particular gene or protein of interest to learn how it functions. It's like the thrill of a treasure hunt for me.

From lab bench to life skills

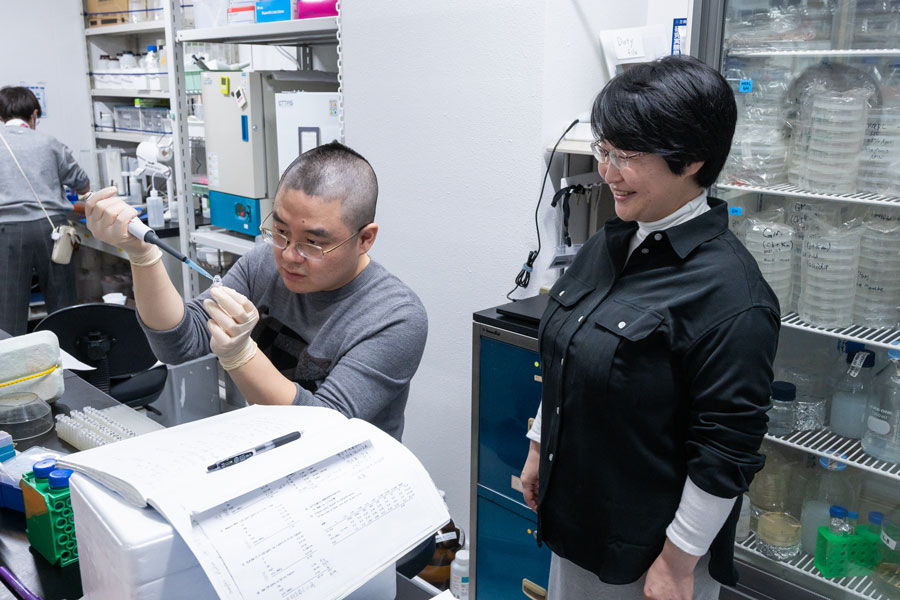

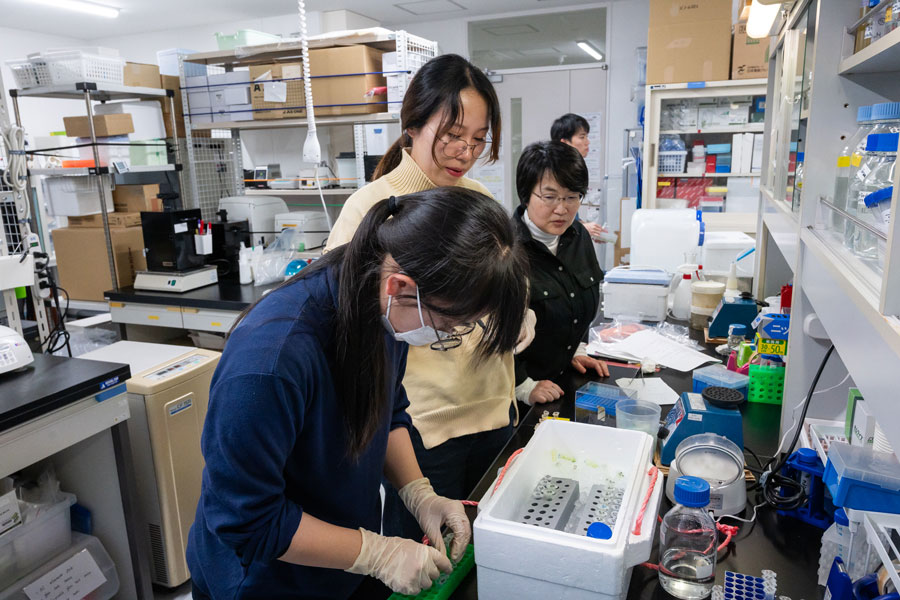

What is it that makes your lab unique?

Perhaps it's our comprehensive approach, which extends from molecular biology to the analytical chemistry of metabolites and elements. And because my research focuses on specific nutrients, I think my lab has more information on particular nutrients and their vital functions than other laboratories.

Is there anything you usually focus on when teaching your students?

The first step of conducting any experiment in plant research is to sow the seeds, and it’s not unusual to wait days for the plants to grow. So, it's crucial to plan the process before beginning an experiment. This means deciding what course of action to take and what to do next in light of the findings. I try to work out this kind of schedule with students who are just starting their research and planning things together at first, but in time, I encourage them to become independent.

Essentially, you aim to help students become self-reliant.

Yes, that’s right. What I like about Japanese universities is that each student has a research topic, which they tackle as budding independent researchers. They formulate a hypothesis for their topic, plan the appropriate experiments, and execute these plans. Sometimes, they succeed, while other times, the outcomes may diverge from what they anticipated. There is a lot to be gained from this process.

What kinds of skills does research build?

First of all, when you engage in research, you acquire the ability to think in a structured and logical way. I think that being able to communicate your ideas clearly is vital to being a working professional, as is articulating your knowledge and abilities. It's difficult to acquire these skills just sitting at a desk. And since a lab consists of a group of people working towards a single goal, I believe it also teaches you how to contribute and interact with others in a way that leads to successful outcomes.

What kind of people do you want your students to become?

I hope they grow into individuals who can make a difference in the world. At university, students are trained to formulate hypotheses based on past research and to think critically about laboratory findings and what they have learned. I'm sure they're likely to become aware of their aspirations and ways of thinking in the process. Once they develop such a habit, they'll be able to voice their thoughts and make decisions about their futures without being swayed by the opinions of those around them. Of course, I’d be most happy if some students end up becoming researchers once they've explored other possibilities (laughs). Aside from that, I wish every student who spends several years with us in the lab all the happiness in life.

What kind of research would you like to pursue next?

I’ve long studied transcription factors, a group of proteins that promote or inhibit the transcription of genetic information written in DNA to RNA. I’d like to clarify their mechanism and create plants, even model plants, that have a high sulfur assimilation capacity while simultaneously being rich in beneficial components. I also want to explore the role of sulfur-containing metabolites in plant growth and study their relationship with other elements.

Navigating life with confidence and conviction

Lastly, do you have any advice for high school students who are still deciding whether to pursue higher education?

In this age of information overload, I'd encourage you to take a moment to visualize what you like doing and what brings you joy. In doing so, your fields of interest and the things you want to do should naturally become apparent. University is not necessarily a means to an end for employment. It’s a place where you can learn about whatever you are interested in at the time. Trust your instincts and move forward with confidence and conviction in a direction that feels right to you.

So, you’re saying it’s important to listen to your heart.

Yes, I think so. That being said, you should also take responsibility for your decisions and commit to them. I feel that the idea of becoming an adult is really the culmination of our experiences. If you keep building on your daily experiences, a better future will always await you. There's no need to look too far ahead and worry that you're not good enough or can't do something. For the young, taking time to discover yourself and asking for advice is not just a right; it's a rite of passage.

Visit Maruyama Lab.