The life and lessons of Dr. Tetsu Nakamura—Part 1: “People deserve love, hearts deserve trust”

Students who took part in Kyushu University’s Nakamura Tetsu Memorial Lecture Series discuss lessons they learned from Dr. Nakamura’s life and work

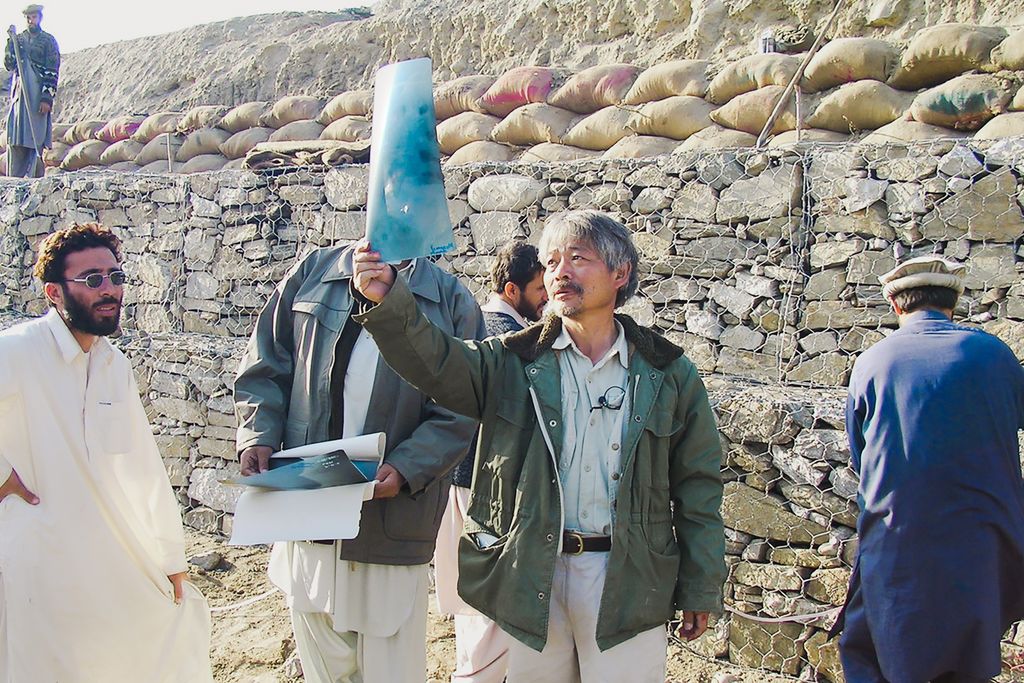

Dr. Tetsu Nakamura (1946–2019) was many things—a physician, a Kyushu University alumnus and University Professor (2014–2019), and the executive director of Peace (Japan) Medical Services (PMS), a non-governmental organization working in Pakistan and Afghanistan—but to the people of northeast Afghanistan, he was nothing short of a modern-day miracle worker.

For over three decades, Dr. Nakamura dedicated all his talents and skills in medicine and engineering to northeast Afghanistan, as wars and environmental disasters hit the region one after another and people lost homes and fields. The unprecedented drought at the turn of the century turned these villages into uninhabitable dryland. Villagers lost hope, but the doctor did not. From 2003, Dr. Nakamura began building an irrigation canal to bring water from the Kunar River into these drylands—water that originated from the glaciers of the Great Hindu Kush Mountains in the west of the Himalayas.

The result of this irrigation project was miraculous. The 27-kilometer-long canal revived what was once called a “valley of death” into a valley of vast green with wheat fields, vegetable gardens, and a park full of roses for people to refresh their war-torn souls. The doctor has left behind in Afghanistan—aside from the canal and its outlets—a team of committed Afghan doctors, a clinic, a farm, a training center, and a guidebook for future Nakamura/PMS-method river engineering.

On December 4, 2019, Dr. Tetsu Nakamura was shot dead along with his driver and four bodyguards in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. The convoy was traveling to their work site, a canal carrying water from the Great Hindu Kush Mountains to the Gamberi Desert.

The doctor died in a place that he loved and adored—Afghanistan, where he had committed himself for over thirty-five years as a physician, engineer, and neighbor. Local villagers would call him “uncle (kaka).” He was cherishing the time with students in Miran Training Center, a new center equipping local communities with knowledge of the PMS method for irrigation development. Drawing on a centuries-old river engineering technology from Japan, the method is a “community-based approach that puts users at the center of all stages of irrigation development.”

To carry on his legacy, Kyushu U has started the Kyushu University Dr. Nakamura Tetsu Project. In June and July 2021, thirty-two students participated in the Nakamura Tetsu Memorial Lecture Series: Passing on the work and the spirit of Dr. Sahib.

The lecturers included Dr. Nakamura’s long-term co-workers at Peshawar-kai, such as Chiyoko Fujita, a nurse who worked at the PMS hospital and clinics in Pakistan and Afghanistan and also the recipient of 2021 Florence Nightingale Medal. The eleven students featured in this two-part article took part in the memorial lecture series.

Helping the weak and respecting all life

“I saw the flags raised at half-mast on campus that December morning. That’s when I realized how big a figure Dr. Nakamura was,” says Muhammad Aulia Rachman, a doctoral student in the Kyushu University Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Global Society.

“I come from Indonesia, the biggest Muslim nation in the world, where Afghanistan has been a sensitive topic in the public sphere. Depending on where and to whom you speak, it’s either Afghanistan is good because they are trying to be Muslim, or it’s totally bad. In Indonesia, debates on how intolerance and religion should play in people’s day-to-day lives are very nuanced.”

Dr. Nakamura has been quite an interesting figure for Rachman. “This guy is a Japanese, pretty much a third-party. Neither from the West nor from a Muslim majority nation. Yet, he is solving social problems in Afghanistan, and profiling what is needed in society. That’s what made me interested. I thought I ought to attend his lecture next time.”

This is what Rachman told himself looking at a flyer for one of Dr. Nakamura’s lectures at Kyushu U’s Ito Campus in early 2019. But that next time never came.

I wanted to listen to him speak, meet him in person, but he was no more.

Following the doctor’s death, the media from around the world released a flood of information on the doctor’s service in Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan. “Everything I heard from the media about Dr. Nakamura matched with the type of humanitarian worker I wanted to become,” says Ibuki Okamoto, a junior in the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation at Kyushu U.

Okamoto was born in 2001, a pivotal year in Afghanistan’s history. Early that year, following an unprecedented drought that struck the region a year earlier, famine was costing the lives of millions. That was when the UN Security Council imposed another round of economic sanctions, as if to kindle the affliction of starving farmers.

Following the new sanctions, all UN aid organizations abandoned projects in Afghanistan. Dr. Nakamura, unwilling and unable to leave the sick and the poor in despair, opened five temporary clinics in Kabul.

Okamoto says, “The doctor’s remark on absolute moral law, I think, best describes the nature of his work. He writes, ‘There is no clear binary between justice and injustice. If there is anything that one could call an immutable moral law, it is that we should help the weak and respect life.’ He truly was a man who respected life.”

Under Afghan airstrikes

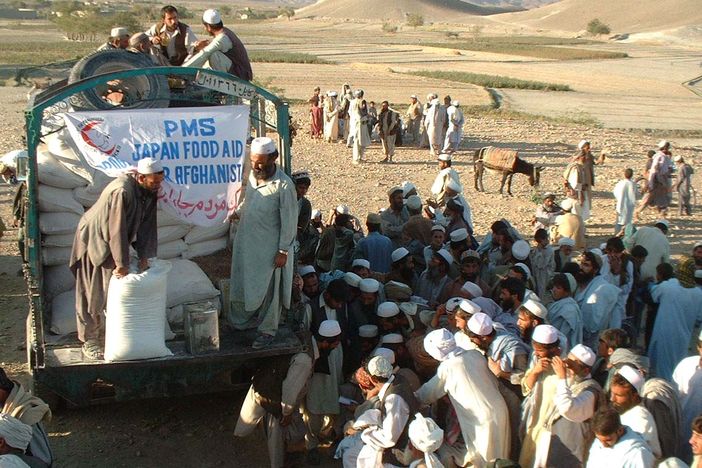

When the U.S. and the U.K. began airstrikes on Kabul following the al-Qaeda–led 9/11 attacks, Dr. Nakamura’s PMS team sent three food convoys in the middle of the airstrikes to distribute food, calling the mission “Afghan Fund for Life.” The funds came from Peshawar-kai, a non-governmental organization founded in 1983 in Fukuoka, Japan, that funds the project of Peace (Japan) Medical Services (PMS), headed by Dr. Nakamura in Afghanistan.

“Growing up in a physician’s family, I learned that being a physician would involve sacrifices,” says Haruki Hokotate, a resident pediatrician and graduate from the Kyushu University School of Medicine.

“You will have little time left to spend for your family. Furthermore, it’s an industry with tradition built on seniority. It’s easier to just continue what your predecessors have been doing than reflect on whether what’s been done is right or wrong. Dr. Nakamura was an exception who did not put profit, comfort, and tradition before conscience.”

Hokotate wants to become a pediatrician and work among children from disadvantaged backgrounds in Asia and Africa.

“Dr. Nakamura’s work in Afghanistan demonstrated, as did Dr. Paul Farmer in Haiti, that infectious diseases could be prevented if people’s living conditions were improved. So while at Kyushu U, my goal was to acquire—in addition to medical knowledge—skills to tackle social issues.”

Hokotate led the student wing of the all-Japan, non-profit organization called “STUDY FOR TWO,” which supports the education of students in Laos and Bangladesh with money earned from selling used textbooks. He was also the head of the student wing of the Japan Association for International Health (JAIH).

“We cannot choose where we are born. This privilege makes me obliged to serve the poor.”

Streams in the wasteland

Ryota Todoroki is a fresh graduate from the Kyushu University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences and currently a student in the Oita University Faculty of Medicine with interests in infectious diseases.

Todoroki realized the value of the medical profession during his visit to a village in Nepal as a leader of a Japanese student organization called “Friends International Work Camp Kyushu” (FIWC Kyushu) and built a community hall with the villagers.

“In rural Nepal, the closest hospital was a dozen kilometers away on foot. I realized that with medical knowledge, I could be more of a resource for both my team and the villagers.”

“Dr. Nakamura used to say, ‘One irrigation canal is worth more than one hundred doctors.’ And with that conviction, he built a 27-kilometer-long canal and contributed to the health and well-being of the people living in the villages along it.”

“The news about the environment we hear today is mostly about doom and gloom, that we humans have destroyed the environment, that it’s too late. But Dr. Nakamura resurrected the environment in such a way that people have returned to their war-torn villages, and are now harvesting wheat, honey, sugarcane, oranges, radishes, and sweet potatoes. This is a story of the environment’s revival.”

His is a message not of doom and gloom but of environmental revival.

In 2003, at age 56, Dr. Nakamura exchanged his stethoscope for an excavator and embarked on a canal engineering project.

“Just by washing with clean running water, many infectious diseases could be prevented. But there was no water for washing to begin with,” recalls Dr. Nakamura in one of many documentaries about his work. “We dug thousands of wells, but the groundwater was becoming scarce.”

The canal turned 3,000 hectors of land back to green pastures, resurrected villages along the way, and began providing subsistence to over 650,000 people.