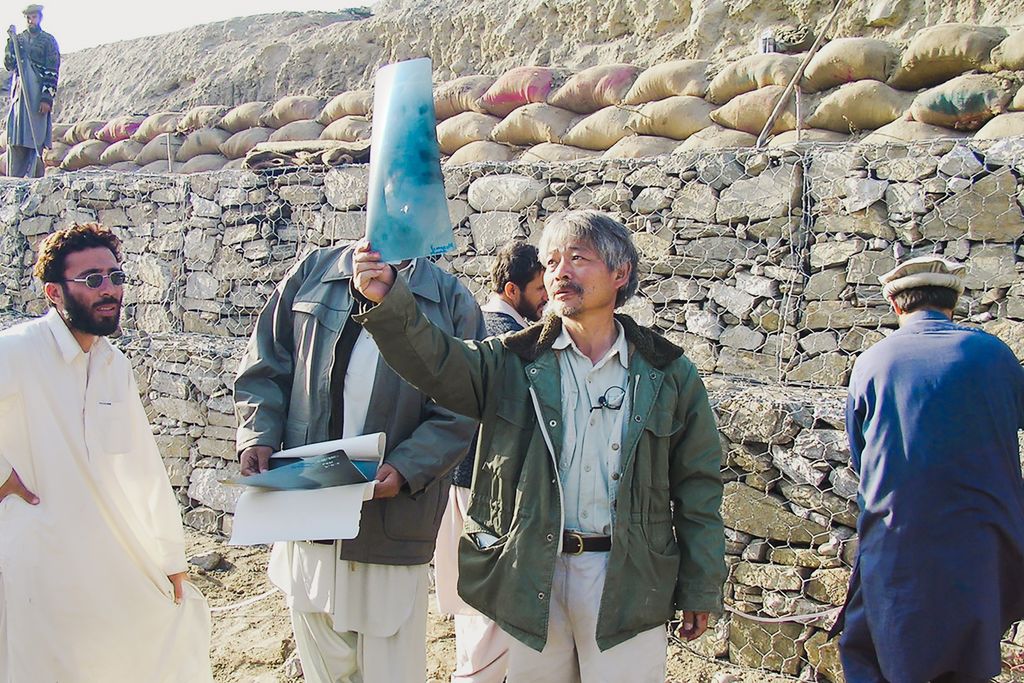

The life and lessons of Dr. Tetsu Nakamura—Part 2: Stars over a hilltop

Students discuss seven lessons for life they learned from the works of Dr. Nakamura

This is the second half of a two-part article featuring students who participated in the Nakamura Tetsu Memorial Lecture Series. For more background on Dr. Tetsu Nakamura’s life, read Part 1: “People deserve love, hearts deserve trust”.

Dr. Tetsu Nakamura wrote extensively in Japanese from Afghanistan, reporting the condition of ordinary people’s lives along with PMS’s monthly activities. When the world condemned parts of Afghans’ unique culture and traditions, he kept writing that people in Japan have much to learn from Afghanistan.

Students who participated in the Nakamura Tetsu Memorial Lecture Series: Passing on the work and the spirit of Dr. Sahib reflected on the messages from the doctor—which are just a handful of the many he wanted to communicate to the youth in Japan—that stuck with them the most.

Lesson 1: Commit long-term to a place and a people

Yohei Shiotsuka is a senior in the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation. “I don’t have a clear plan for my future yet, but one thing is sure. Regardless of the profession I choose, I want to keep Nepal close to my heart.”

Shiotsuka visited Nepal as a volunteer worker to help rebuild the Himalayan villages hit by the 2015 earthquake. Shiotsuka has chosen Nepal as his research field in anthropology and area studies for the past three years.

“One could say that my interest in Nepal is accidental, just like Dr. Nakamura’s case, who traveled to the Hindu Kush Mountains in Pakistan in pursuit of a rare species of butterfly. But I see my meeting with Nepal almost as destiny. I like thinking and studying about Nepal, its people, and traveling there,” says Shiotsuka.

“I think a long-term commitment to a place is important. By relating to and holding on to that Himalayan nation, I hope to contribute to the fields of area studies, international development, South Asia Studies, and many more in the future.”

Lesson 2: Sacrifice and celebrate life

“He chose to go and live among drought-stricken farmers in a country that the world had turned its back to. I wonder from where the doctor got such a wellspring of energy,” says Airi Terada, who is completing her master’s in forest management in the Graduate School of Bioresource and Bioenvironmental Sciences this year.

It was only after she read a book on Mother Teresa in the 3rd grade that she learned what extreme poverty looks like and what a life of dedication and service means.

“I would look at my parents’ age group, those in their forties and fifties, and wonder, ‘Would they sacrifice their lives like Mother Teresa?’ I thought it was very unlikely that they would do so.” Terada was happy to learn about Dr. Nakamura’s work in Afghanistan. “He was my contemporary while Mother Teresa was a woman from history books.”

“It may be the doctor’s experience of growing up in war-torn Japan—the world of scarcity and hard work—that gave him such herculean energy,” says Terada.

Another source of such miraculous energy, Terada thinks, may have resulted from Dr. Nakamura’s close relationship to nature. Life in Japan, as it is today, is rather distanced from nature, and many people are too busy to even look at the stars at night.

Terada says, “All that I wish is to celebrate life and have a good time. This is my last year in the master’s program. If I could be selfish and not worry about others or searching for a job, all that I desire is to lie on top of a hill at night and look at the stars.”

Lesson 3: Be moved by small things

“I was interested in what led the doctor to Afghanistan. He was born in Japan in an affluent family. Why did he choose to quit a life of comfort and go to Afghanistan?” asks Saki Okada, an engineer who earned an MSc in engineering in March 2022 from Kyushu U.

Okada thinks she found an answer to this question in Dr. Nakamura’s book From an Afghan Clinic (1993): “In Peshawar, the people and their warmth I encountered in the streets were so consoling that I almost forgot about the terror and violence happening at that time.”

“The streets and the warmth of the people living in them. That’s what attracted the doctor to Pakistan and Afghanistan. Being moved by such feeling—small, compared to the enormous work that he accomplished—the doctor kept returning. I think the doctor was not that different from me, because I too am moved by such small things. It was reassuring to find in him a sensitivity similar to what I find within myself.”

Lesson 4: Do not lose sight of the poor

“I am interested in Dr. Nakamura because I want to know what his messages mean to us today,” says Aki Nonaka, a junior and history major in the School of Letters.

“His thoughts cannot be contained by any political partisan argument. That was something refreshing,” says Nonaka. “What the doctor was most critical of was our indifference toward the real condition of the poor.”

When Taliban destroyed the Bamiyan Buddha statues and the world began condemning such acts, Dr. Nakamura wrote that millions were dying due to famine in Afghanistan at that time and that he and his team had no time to waste in joining the accusation. It seemed to the doctor that a world that was emphasizing the conservation of the cultural heritage of humanity was astonishingly silent when it came to the plight of famine-stricken Afghan villagers.

Lesson 5: Be honest

“What struck me after reading Dr. Nakamura’s books is that there are no lies in him. I don’t agree with all that he wrote, but I find no lies in his words. That’s why his words are worth trusting,” says Tomokazu Iwabuchi, a doctoral student in the Graduate School of Human-Environment Studies.

Iwabuchi, who aspires to become an entrepreneur, learned from Dr. Nakamura the secrets of winning ordinary people’s hearts.

“In his writings, the doctor would equally address the ugly side of human nature—such as grudge, jealously, and lust—along with positive characteristics. Honesty was one of his great characteristics. He never pretended to be someone else other than himself or feeling something else other than what he was feeling. The secret of his success was being sincere to himself. Since he was true to himself, he would also accept everyone just as they were.”

I don’t agree with all that he wrote, but I find no lies in his words.

Lesson 6: Keep promises

“I find no contradiction between his words and actions. What he said was what he did. Sincerity is definitely one thing that distinguishes him from many other international aid workers,” says Sara Lake, a sophomore in the School of Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation.

“He could have asked a big construction company to build the canal he was building. Instead, he carried stones himself, side by side with the Afghan workers. Despite his age, he volunteered to do physical labor. The philosophy behind his colossal projects and his sensitivity toward the culture and condition of the people definitely stand out. He kept promises that he made with Afghan villagers.”

A man with no contradiction in what he said and what he did.

Lesson 7: Be unconventional and versatile

“The words of Dr. Nakamura that resonate well with me are, ‘Diseases can be cured later. First you need to survive!’” says Daichi Muraguchi, a medical student in the School of Medicine.

“I imagine if such words were uttered in a hospital in Fukuoka City, people would think you are failing as a doctor. But the place these words were uttered was drought-stricken Afghanistan, where people were suffering starvation and lacked physical strength.”

“I too chose the medical profession with the same desire as Dr. Nakamura to save the lives of as many people as possible who come to seek my help. In the case of Dr. Nakamura, in his attempt to save more lives, he decided to build a canal, which made the land fertile again and restored agricultural production. People can now get nutrition from the produce. By doing so, he was able to save more people than he could have done with medicine.”

“It is such a versatile way of approaching diseases that I want to draw ideas from. I want to practice medicine, but at the same time, I am now interested in developing vaccines. Vaccines for tuberculosis, especially. Let’s say I live another 50 years. I can save more lives by introducing new medicine than meeting patients one by one in those fifty years.”

“Furthermore, what Dr. Nakamura began in Afghanistan, the seed that he planted, is still being carried on there. It means it is contributing to children who are yet to come. So I am interested in research as well as clinical practices.”