Composing Letting Nature In

Daryl Jamieson is a composer in the American experimental contemporary music style, informed by Buddhist and the Kyoto School of philosophy. This month is a performance on the Goto Islands, famous for the World Heritage Sites of the “Hidden Christians”.

Daryl Jamieson is a renowned composer known for his profound incorporation of Buddhist philosophy and teachings of the Kyoto School. His remarkable expertise extends to the detailed analysis of nō treatises by Zeami Motokiyo and Konparu Zenchiku. With a strong commitment to global collaboration, Jamieson has led numerous international projects, most notably his contribution of original scores to "The Seaweed Gatherers" project in partnership with the University of Glasgow. Continuing the rich legacy of the utamakura tradition, which spans over a millennium, Jamieson skillfully composes music inspired by illustrious locations throughout Japan. His compositions evoke the essence and spirit of these famous sites, captivating audiences with their evocative melodies and immersive harmonies.

What is your area of expertise?

My area of expertise is music composition, generally in the American experimental style of contemporary music tracing back to John Cage.

Why did you decide to pursue composition?

I have been composing since I was a child, and studying music composition since my undergraduate years, and it has remained my main area of focus throughout. My music is deeply rooted in philosophy, particularly in the Cageian style. However, since coming to Japan, I have developed a secondary specialization in Japanese philosophy, specifically Japanese aesthetics, informed by Buddhism and the Kyoto School as it has been explored over the past thousand years.

The primary connection between these two interests lies in my fascination with nō, a traditional Japanese performing art. In particular, I am captivated by the works of Zeami Motokiyo and Konparu Zenchiku. Zeami can be considered one of the early pioneers of nō, as he incorporated various performance styles that had previously been known by different names. Interestingly, he did not refer to it as "nō" initially, but the term eventually crystallized during that period.

Both Zeami and Zenchiku hold significant importance for me. Zenchiku had a strong religious and spiritual focus, surpassing even Zeami in this regard. They produced numerous treatises and theoretical works, which is rather uncommon for musicians and actors from the medieval era.

That's amazing that their old texts and compositions remain!

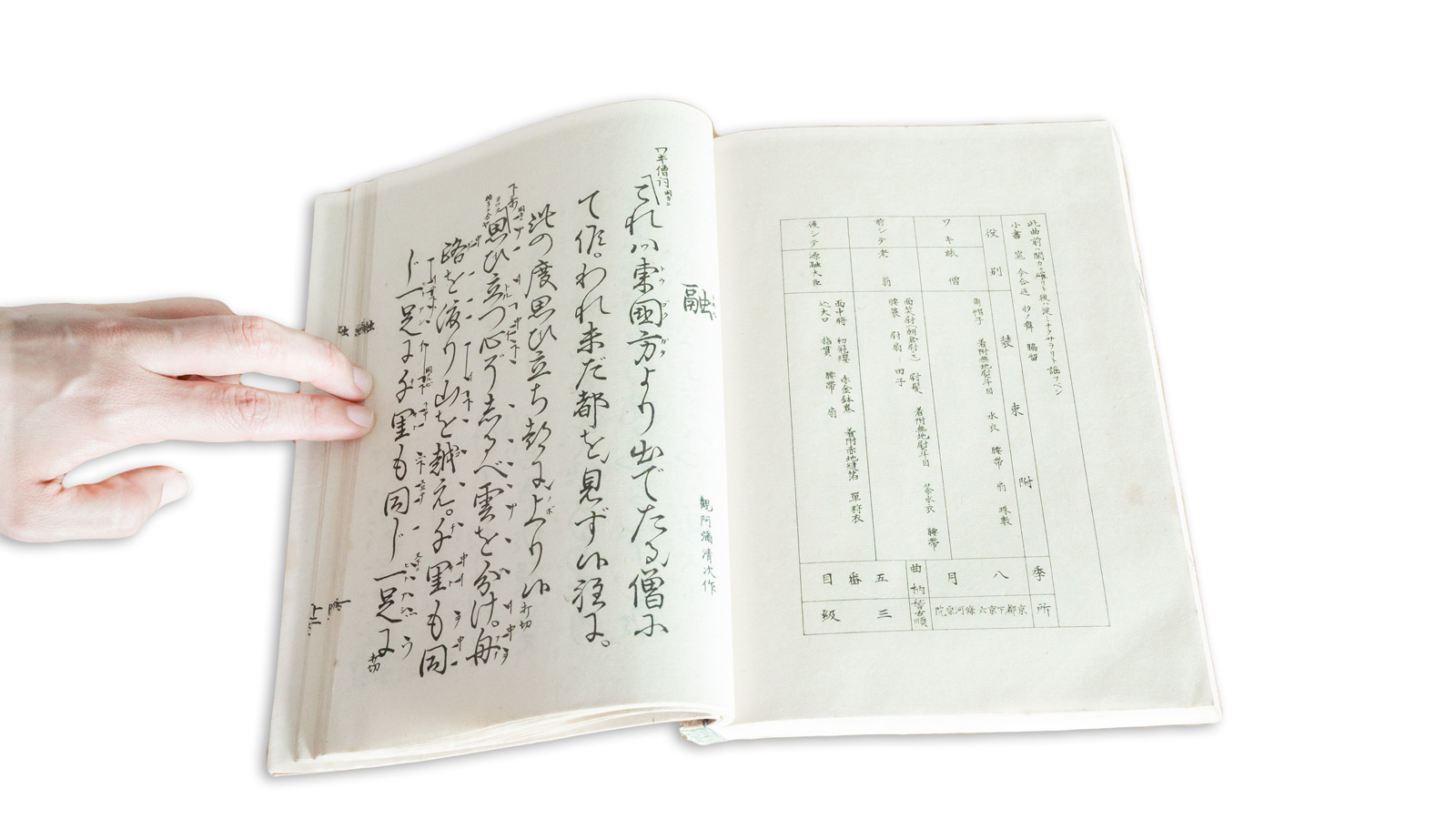

Indeed, attributing specific contributions in nō can be challenging due to its collaborative nature. It can be likened, to some extent, to opera, although they differ in various ways. Nō encompasses not only music but also words, acting, and dance. The performance tradition itself has evolved over centuries, making it difficult to ascertain individual roles. However, treatises offer a clearer attribution as they are typically signed and in the author's handwriting. These treatises provide objective descriptions of the artist's intentions.

Zeami authored 23 treatises, while Zenchiku wrote 5. Zenchiku dedicated decades of work to his main treatise titled "Rokurin Ichiro," meaning "six circles, one drop." Multiple versions of this treatise exist, each significantly different from the next, showcasing its evolution. Although Zenchiku wrote fewer treatises, he repeatedly revised one that expounds on the artist's objectives, delving into philosophical and spiritual perspectives. In Zenchiku's case, he emphasizes the significance of art in the world and its contribution to the spiritual community.

The arts hold a sacred role in connecting humans not only to the divine but also to the wider world. In three of Zenchiku's works, the main character is actually a plant. Other non-human entities, such as seaweed, are personified as well. These spiritual encounters between humans and non-human beings, humans and plants, and humans and non-sentient entities, including gods, are staged by Zenchiku. For him, this was not merely a dramatic exercise but a profound spiritual endeavor.

What is utamakura?

Utamakura is a concept that utilizes art as a medium to connect the audience, including myself as the performer and anyone who listens, to a specific place. Derived from the Heian period, this poetic concept is primarily employed in poetry. Utamakura refers to a place name that, over the centuries, accumulates meaning and significance through its repeated use in poems. Certain places become associated with particular moods, scenes, or seasons.

In classical Japanese poetry, there exists a realm of words specifically suited for particular seasons, while others are deemed inappropriate. This tradition carries on through haiku and, specifically in the Heian period and subsequent years, the utilization of utamakura gradually evolved. Rather than symbolizing the actual location, the focus shifted towards the symbolic significance of the place, resulting in intricate associations and references. This intertextuality became prevalent, and by the Kamakura period, notable poets like Fujiwara Shunzei, a highly regarded nobleman who contributed to the imperial anthologies, began exploring the connection between poetry and Buddhism.

What caught my attention was Shunzei's assertion that without the poem, one cannot fully grasp the essence of the actual thing. In essence, poetry transcends mere language—it becomes a vehicle for conceptualization. Shunzei made this observation roughly 500 years after the inception of utamakura. For example, if the utamakura used is "Mount Yoshino," a famous cherry blossom destination in Nara, uttering the word "Yoshino" evokes a shared understanding among those educated in classical poetry. The mention of Yoshino brings to mind cherry blossoms, a specific season, and even conjures imagery of snow, as the white blossoms can resemble a snow-covered landscape from a distance. This visual illusion occurs.

Shunzei's point is that visiting the actual mountain may not necessarily match the descriptions found in the poems. He argues that the poetic portrayal holds a more profound truth than what meets the eye. There is a disconnect between our sensory perceptions and the accumulated wisdom spanning five to six centuries of poetry.

This accumulated wisdom aligns with the Buddhist concept of ultimate reality. Zeami and Zenchiku also employed this idea in their nō plays. Close to half of their nō plays are titled after specific places, incorporating the most renowned poetry associated with those utamakura locations. Often, the plays revolve around a traveler arriving at the place and expressing astonishment or doubt, questioning if it truly matches the fame attributed to it. Then, a local character appears, often revealed as the ghost of a person or, in Zenchiku's case, the spirit of a plant or the seaweed tied to the place. The second half of the play usually features a dance where the true beauty and grandeur of the location are unveiled, surpassing the initial observations of the traveler.

Through the lens of art, one can overlay a deeper understanding onto what our senses perceive or what we hear. This includes historical knowledge, cultural references, and a comprehensive understanding of a place beyond a superficial visit. By incorporating layers of interpretive knowledge, a location, even if not inherently beautiful, gains meaning and significance. Furthermore, in our current era marked by environmental degradation, this approach can highlight the deterioration of a place and remind us of its former beauty.

For me, utamakura now signifies creating recordings, particularly field recordings, not limited to Japan. I choose places that are often not conventionally regarded as poetic or associated with nō and similar art forms. Many of these locations have been impacted by traffic or transformed into industrial areas, while rivers have been concreted over. Through my recordings, I aim to emphasize the contrast between the past beauty of these places and their current state, even if the recordings themselves may not possess traditional ideas of “beauty”. The project also serves as a remembrance, as I accompany the videos and audio with layered music that evokes a sense of nostalgia and reflects the past essence of the place. The series consists of six completed works, with a projected total of seven. I am yet to finish one of them.

Could you tell us about your paper, Spirit of place: Zeami’s Tōru and the Poetic Manifestation of Mugen?

My most recently published paper, titled 'The Spirit of Place,' focuses on the concept of utamakura in a specific nō play called Tōru. The play revolves around a complex web of utamakura, where typically only one utamakura and its associated poem are featured. However, in this play, Zeami pushes the boundaries of the form he created, demonstrating great erudition. He incorporates a large number of utamakura, about 14, in a scene at the end of the first act.

Kyoto and the Kansai region are rich in utamakura, and the play highlights various utamakura sites, pointing from east to south to west. It plays with the idea of utamakura and showcases the abundance of these locations. Furthermore, the play is set in a garden, which in itself is considered an utamakura and is designed to mimic a different utamakura in present-day Miyagi Prefecture. The concept of time is complex in the play since the main character is a ghost who lived in the 9th century, while the play is set in the 15th century. The garden, although in ruins, is depicted by the ghost as if it were still intact, evoking its 9th-century heyday. The ambiguity arises as to whether the ghost believes it is in Miyagi Prefecture or if it perceives itself in the past, or perhaps both simultaneously.

The paper explores how these textual ambiguities create an unsettled atmosphere, with Zeami intentionally employing a complex web of associations to evoke ambiguity and unrest in the play. What sets my contribution apart from other scholars in Japan, who have discussed similar topics, is that I approach it from a musicological perspective, examining the rhythmic structure of nō, particularly in those scenes where it adds a layer of unsettledness. Nō music lacks a firm pulse and constantly fluctuates in speed, even during climactic moments, where brief periods of steadiness are interspersed with acceleration and deceleration.

The paper argues that Zeami not only utilizes textual ambiguity but also complements it with the music, creating a cohesive artistic experience. Simply studying the text, as is common in nō scholarship, is insufficient; nō must be considered as a performing art, emphasizing the musical performance and rhythmic elements that contribute to the audience's sense of discomfort, tension, and eventual resolution. This paper marks the first step in exploring this direction further.

While this particular paper focuses on a play featuring an old man, a famous dandy from the aristocracy, my subsequent research delves into nō plays with non-human characters, particularly by Zenchiku. These plays employ more spiritual language, creating unresolved tensions that differ from Zeami’s more typically resolved conflicts. They present a greater level of complexity and perhaps realism. However, this research is ongoing.

The main argument of this paper is that ambiguity in nō offers an unsettling atmosphere that can trigger surprise and shock. By immersing oneself in the fluctuation of time, movement across locations, and the constant rhythmic shifts, a disoriented state is achieved. It is within this disoriented space that new thoughts and creative ideas can emerge. In the religious interpretation, such ambiguity provides a glimpse into ultimate reality, a perspective rooted in Buddhist philosophy. Alternatively, from the perspective of the Kyoto School of philosophy, it reflects absolute nothingness or a hollow place. It presents the notion that our perceived reality may have cracks, and acknowledging our limited understanding is the first step towards a broader comprehension of reality, whether it be in a religious or humbling sense. Humans cannot fully comprehend the intricacies of existence; our brains and sensory faculties restrict our understanding. That is the essence of this paper.

Can you elaborate about your paper Field Recording and the Re-enchantment of the World: An Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Approach?

The conclusion I have reached in this paper is reminiscent of the previous discussion on the division between conventional reality and ultimate reality in traditional Buddhism. Ueda Shizuteru, a philosopher from the Kyoto School, emphasizes the term "hollow expanse" to depict ultimate reality. This translation, as rendered by Brett Davis, beautifully captures the essence, as "hollow" suggests a space that holds potential or can be filled, without the negative connotations associated with words like "nothingness" or "void." It is essential to note that ultimate reality is not a philosophy of nihilism; rather, it represents a playground where limitless possibilities exist.

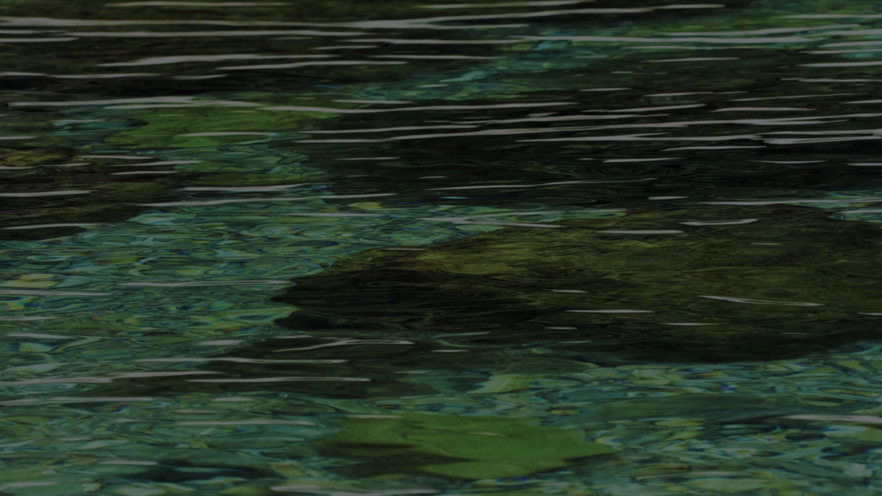

In my paper, "Spirit of Place," I argue that a similar experience can be achieved through the ambiguity created in nō theater. Similarly, in my project "Enchantment of the World," which focuses on field recordings, I propose that this contemporary medium can evoke a comparable effect to nō. Unlike nō, which may require knowledge of classical Japanese and a deep familiarity with classical poetry to fully appreciate, field recordings offer immediate immersion. One artist, Tsunoda Toshiya, a renowned field recording artist and professor at Tokyo University of the Arts, employs simple yet unconventional techniques in his recent works. Initially, his recordings may sound like realistic, documentary-style representations of nature. However, upon closer listening, subtle moments of hollowness or gaps in perception become apparent, stemming from the spacing or unconventional placement of microphones. This unexpected realization engenders a sense of surprise and shock, akin to the experience of visiting a historically significant place that no longer aligns with one's expectations.

While Tsunoda’s intentions may not explicitly align with my interpretation, his work resonates with the concept of disconnection and the potential to broaden our understanding of reality. Human perception of reality does not encompass an absolute representation of what reality truly is. Tsunoda’s recordings focus specifically on sacred locations (a bit like “utamakura”) such as the Somashikiba, which are graveyards of farm animals. These places held spiritual significance in the Edo period, where animals were buried and markers with cow or horse heads were placed. Tsunoda’s recordings in these sites possess not only a spiritual quality but also serve as reminders of forgotten historical and cultural connections between humans and nature.

The concept of re-enchantment lies in utilizing audio as a medium to awaken the senses, evoke wonder, and reignite interest in locations where significance has been disregarded or lost in contemporary society. Tsunoda purposefully selects places of religious and natural importance that have been overlooked or sacrificed. His art aims to restore a sense of magic and wonder to these forgotten places. I believe my work aligns with a similar objective, albeit with a focus on different types of locations. I am indebted to Tsunoda’s contributions as my research builds upon his endeavors.

Can you tell us about the Goto Maritime Silk Road Art Festival?

The upcoming premiere of our project is just around the corner, with the first performance scheduled in Fukue, Goto city, on July 15th, followed by another performance on the 17th in the second largest city in the northern part of the archipelago. This project has been a long time in the making, spanning over two years. It all began with my desire to collaborate with Kimihiro Yasaka, a pianist who commissioned the piece and will be giving the premier performances next month. Kimihiro, originally from Sasebo, Nagasaki, has spent his adult life in Montreal, while I, being Canadian, have made Japan my home after completing my university studies. Our collaboration has evolved over time, with him recording one of my pieces and releasing it in 2020, and me writing a short piece for him, which he premiered last year in Nagoya.

The current project is a significant undertaking, with a duration of approximately 75 minutes. We selected Goto as the performance location for both practical and conceptual reasons. Goto is a fascinating place—an island chain located off the coast of Japan, between Kyushu and China. Its remote nature has given it a distinct history and unique plant species, creating an ecology and ambiance quite different from Kyushu, despite being politically part of it.

Furthermore, Goto holds cultural significance due to its proximity to mainland Asia. It was among the first places settled in what is now the modern nation-state of Japan, as evidenced by archaeological findings. People from mainland China reached Goto during the Jomon period, making it an early settlement site even before Kyushu. The island's long history of human habitation sets it apart from other regions in Japan.

Goto also served as a stopover for the Kentoshi, Tang Dynasty missions that traveled to China. Stones with carvings and mooring sites remain as archaeological evidence of these voyages. Kukai, the founder of Japanese esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyo Shingon sect), embarked on one of these missions and established temples in Goto. This historical narrative intertwines religious and archaeological elements. Additionally, during the Edo period, Christianity was prohibited in Japan, leading to the formation of refugee Christian communities in Goto. These communities, while facing persecution, were able to practice their faith in isolation for approximately 250 years, making Goto an intriguing place with layers of spiritual and historical significance.

The concentration of churches, many of which are recognized as world heritage sites, adds to Goto's appeal. Its geological and ecological characteristics, coupled with its spiritual and historical context, make it an ideal location for our project. Additionally, the concept of the archipelago as a liminal space intrigues me. Defining an archipelago raises questions about its boundaries—is it defined by the islands themselves, the surrounding ocean, or the connection to the mainland? These ambiguities reflect my artistic interests, as seen in nō plays and Tsunoda's field recordings. Such ambiguity allows for the exploration of the limitations of the human mind and has the potential to evoke wonder and curiosity, ultimately creating a profound encounter with the place.

In terms of process, I visited Goto four times over the past year, spending three or four days during each visit. I captured audio and visual recordings on all the main islands, including most of the inhabited ones. These recordings will be featured alongside the piano performance. Similar to nō plays, the piano represents the visitor, while the field recordings symbolize the spirit of the place—the central character in the dance of the nō. The drama unfolds through the interaction between the outsider (the piano) and the sounds and visuals of each location, creating what I hope is a captivating experience.

It sounds like a perfect location for your work given the history of intersection with spirituality of the West and East

Yes, Goto's complex and spiritual history truly makes it a special place. The preservation of Christianity despite persecution for over two centuries is a testament to the resilience and determination of these communities. The coexistence of Eastern and Western influences is evident in Goto, and while the Christians have kept their traditions and sense of isolation, their churches have become significant world heritage sites, contributing to the islands' economy.

It's interesting to note that even today, the Christians in Goto maintain their distinct identity and prefer to live in small, isolated communities rather than moving to larger cities. They have managed to preserve their faith and culture, which adds to the unique character of the place.

The process of declaring these churches as world heritage sites raises questions about the extent of consultation made with the individual isolated communities. The boundary between the village sites and the church areas remains clearly defined, as indicated by the signs guiding visitors along designated paths. This emphasis on maintaining the separation between the two reflects the desire of the communities to be left alone and preserve their way of life.

The hidden Christian elements in Nagasaki and the intriguing museum space in the Dozaki Church in Fukue adds another layer to the story. The blending of Christian and Buddhist imagery, such as a statue of Kannon holding a baby with a little cross, highlights the efforts made to disguise Christian symbols to avoid persecution. It's a reminder of the challenging times these communities faced and the creative ways they adapted to survive.

Goto and Nagasaki both offer rich historical and cultural experiences, with hidden narratives waiting to be discovered. It's fascinating to explore these places and learn about the complex interplay of religions, traditions, and the resilience of the people who have shaped their communities over time.

You grew up by the ocean in Halifax and have lived by the ocean in Zushi and now in Fukuoka. How has Fukuoka informed your work?

I appreciate Fukuoka's coastal location and enjoy visiting the Ito Campus because of its proximity to the ocean. Being by the ocean can provide a calming and inspiring environment. Chance and collaboration play important roles in my artistic process, influenced by the ideas of John Cage and the concept of "letting nature in." Field recording allows me to incorporate sounds that occur naturally, without conscious selection, thereby embracing the serendipity of the environment. This aspect of my work aligns with collaborations with other human performers.

One of my ongoing projects, "The Seaweed Gatherers," involves collaboration with Scotland-based artists such as Graham Eatough and Meik Zwamborn. The collaboration with Glasgow University and its strategic research partnership with Kyushu University highlights the wider program and encourages collaborations between artists. In this contemporary retelling of Zenchiku's nō play set in Kyushu at Mekari Shrine, we explore themes of breaking barriers and reimagining the Eucharist. Miek Zwamborn contributes stories and cooks seaweed on stage, symbolizing the breaking of the fourth wall and offering food to the audience. Field recordings, including those made at Mekari Shrine, are also incorporated into the piece. While the project is still in progress, there was a work-in-progress showing in Glasgow last year, and I hope to further develop and perform it in Kyushu in the future.

In the Goto project, I not only use field recordings in situ but also incorporate improvisational elements that Kimihiro adds to the score. The process involves a three-step collaboration: I make a field recording, send it to Kimihiro, and he responds musically with piano. Then, I listen to his piano recording and write the piano part in response. This layered process introduces contingency and collaboration into the composition, even for the parts we have written down. Embracing this openness and relinquishing control is an essential aspect of my approach as a composer. Rehearsing with Kimihiro in Fukuoka prior to the performances further enhances the collaborative process and preparation.

Overall, my artistic practice involves embracing chance, collaborating with other artists, and incorporating various elements into work, whether it be field recordings, improvisation, or responses to other musicians' performances. I hope this multi-layered and collaborative approach adds depth and richness to the compositions.

You can attend Prof Jamieson’s events below:

Goto Maritime Silk Road Art Festival (July 15th and 17th): https://goto-art.com/pianoandnature2023/

*The tickets to this event are no longer available.

Tickets for the Ohashi concert (July 23nd): https://nonhumanmusic1.peatix.com

For more information on Dr. Jamieson and his works:

http://daryljamieson.com

http://atelierjaku.com

http://ememem3dots.com

Daryl Jamieson (2022) Spirit of Place: Zeami’s Tōru and the Poetic Manifestation of Mugen, Japanese Studies, 42:2, 137-153,DOI: 10.1080/10371397.2022.2101991

Daryl Jamieson, Field Recording and the Re-enchantment of the World: An Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Approach, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Volume 79, Issue 2, Spring 2021, Pages 213–226, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaac/kpab001