Streamlining construction of safer buildings

with Assoc. Prof. Shintaro Matsuo

Have you ever tightened a screw? How about welded a joint? If you can only say yes to the first, you certainly are not alone. Countries around the globe are facing a shortage of welders that could begin to delay construction projects if it worsens.

To overcome this bottleneck, Shintaro Matsuo, associate professor at Kyushu University’s Faculty of Human-Environment Studies, is exploring options for making the construction process as easy as twisting a bolt—while at the same time ensuring the building structures themselves are as safe as ever.

“Welding requires specialized skills and continuous training to keep up with advances in construction materials, but anyone can twist a bolt,” says Matsuo. “Completely eliminating welding is unnecessary, but switching some connections to high-quality bolts could greatly simplify and speed-up construction.”

For the estimated 13,000 urban buildings constructed daily around the world, safety and ease of construction are key considerations. Stronger materials often improve a building’s structural integrity while also reducing its weight, but such advances frequently come with a tradeoff in terms of stricter requirements during construction.

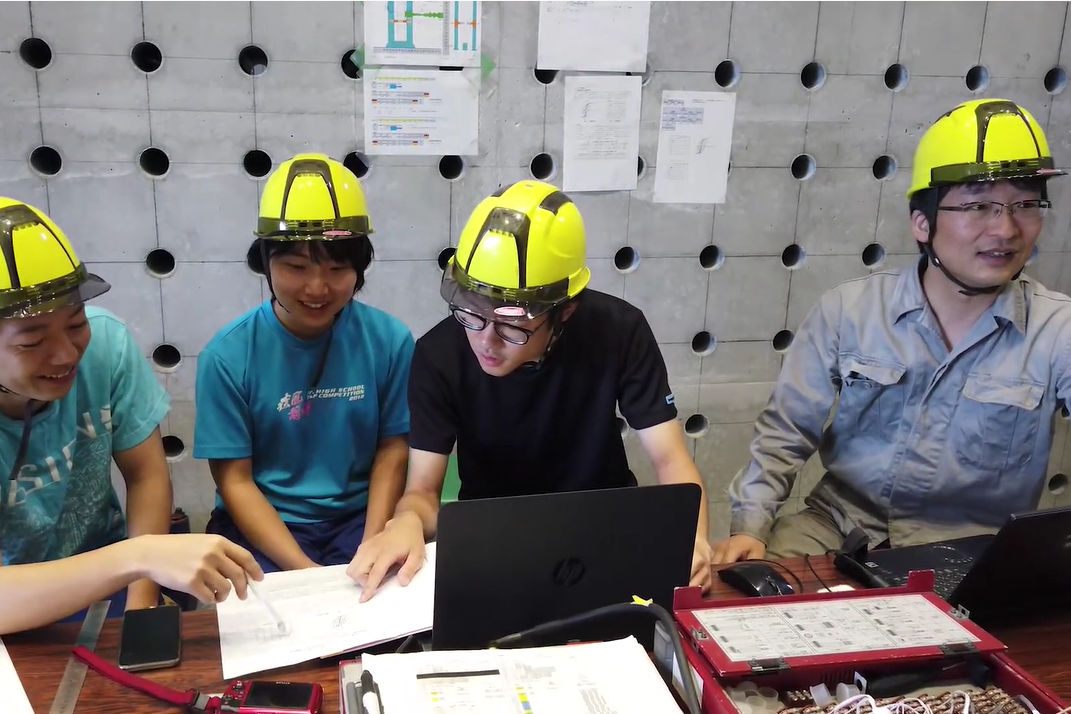

Thus, Matsuo has been focusing his attention on developing and evaluating construction techniques that can relax these restrictions. Using bolts keeps more of the precision and skilled work—such as bolt production and welding of diaphragms for bolting beams to columns—in the factory, greatly reducing on-site labor.

“Though the general idea is simple, no one has yet to find the right construction design, method, and guidelines for systematically and broadly applying such an approach. However, the potential is tremendous if breakthroughs can be made,” comments Matsuo.

Another construction technique Matsuo is hoping to make easier to implement is concrete-filled steel tubular (CFT) structures, which have drawn attention in skyscraper construction for their excellent performance. Concrete improves strength while reducing the amount of steel needed, and the permanent tubes reduce labor associated with dismantling temporary formwork. However, the concrete filling is a sensitive process.

“At present, only a few companies can control the filling process strictly enough to achieve the high quality needed,” says Matsuo, “so we are looking for ways to loosen these restrictions so more people can do it.”

Welding is also needed when fabricating CFT members. Though high-strength steel is desirable for fabricating the tubes, welding seams with filler materials of similar strength to create the strongest possible joints is a complex process.

“However, when the entire structure is considered, the benefit of a high-strength joint versus a low-strength one can be limited in certain situations,” explains Matsuo. “By understanding where weaker joints can be tolerated while still maintaining the desired integrity, we may be able to use simpler welding techniques.”

To study what changes can be tolerated and predict how the various construction techniques will fare in the real world, Matsuo and his group are performing loading experiments and modeling. Physical tests to identify failure points can be done using equipment on campus, and modeling helps to understand exactly why parts behave how they do and guide new designs.

However, such tests have their limits.

“Phenomenon studied by experiments are limited by a researcher’s assumptions and imagination. In the real world, the possibilities are endless,” comments Matsuo. “To bridge this gap, surveying actual failure in building structures is invaluable.”

As a part of such activities, Matsuo joined a working group that evaluated building damage caused by the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes, a series of earthquakes originating near Kumamoto City, which is about 100 km south of Kyushu University.

“While the enormous damage caused was unfortunate, we have a duty to learn from the experience to further improve building safety,” says Matsuo.

Through continued research efforts like these, Matsuo hopes to make future buildings safer for the people in them and less demanding on the people who build them.