A fear of insects overpowered by a curiosity of the unknown in the fight against vector-borne diseases

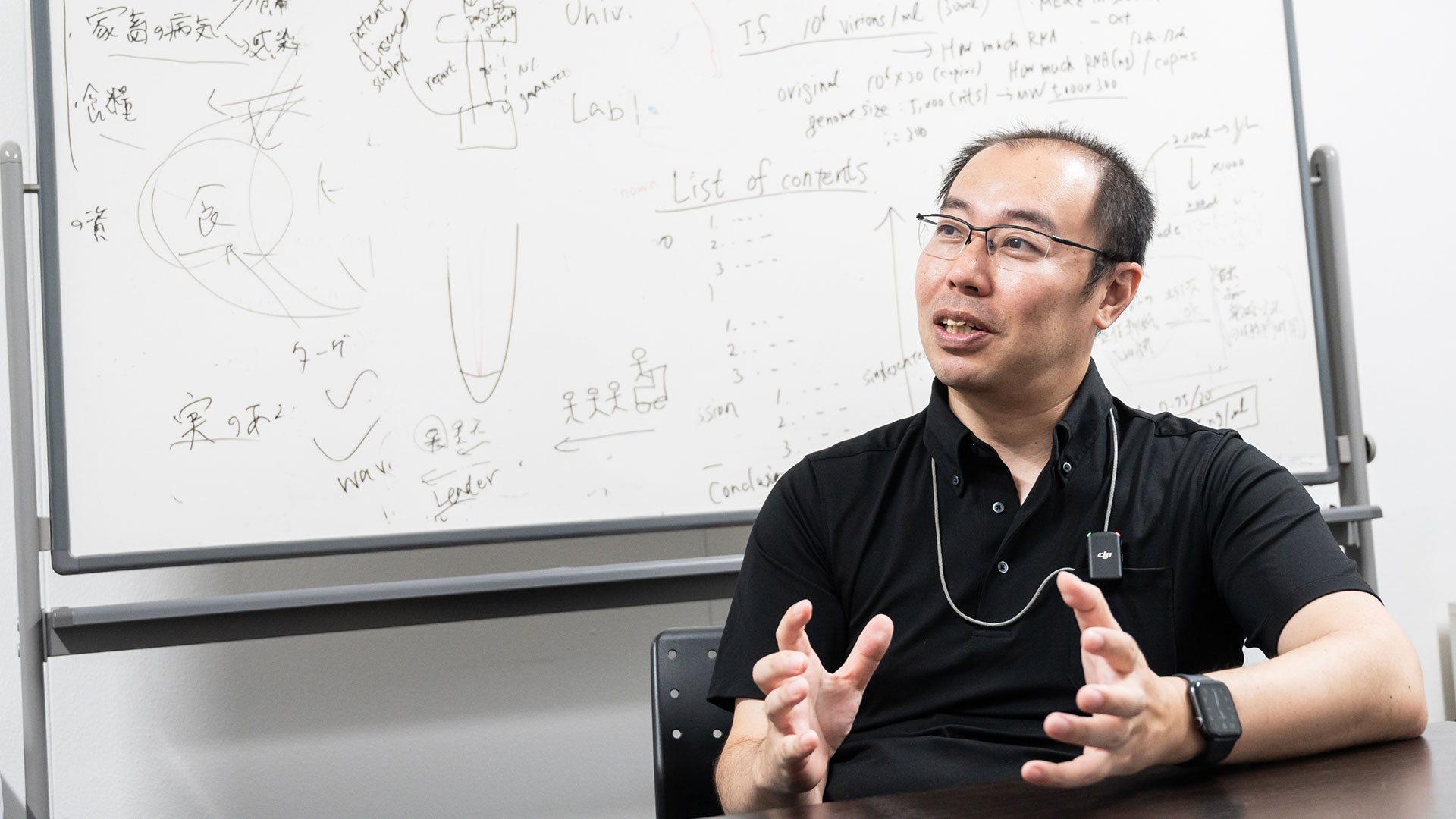

Discover the Research: Article 6 – Ryosuke Fujita, Faculty of Agriculture

When people hear “insect research,” their thoughts may turn to rare, never-before-discovered species. But the research being done by Associate Professor Ryosuke Fujita of the Faculty of Agriculture involves infectious diseases transmitted by common insects and arthropods such as ticks, mosquitoes, and flies. We heard from Fujita about his research on pests that harm animals and human beings, why he chose it, and its significance.

The original Japanese version of the interview can be found here.

Defeating pests harmful to humans and animals

First, could you tell us about your field and what your research focuses on?

My field of research is sanitary entomology, which focuses on combating insects that can negatively impact human and animal health. Specifically, the harm caused by insects primarily involves spreading diseases, which we refer to as vector-borne diseases. The most well-known examples are dengue fever and malaria, both of which are transmitted by mosquitoes. But there are many other infectious diseases in the world that are not nearly as well-known. We study the various diseases spread by different insects, such as ticks, mosquitoes, and flies, to identify what infections exist and develop strategies to combat them.

Why did you decide to pursue a career in sanitary entomology?

Maybe it’s just that I hate insects (laughs). I’m only half joking. I originally studied molecules and genes, and the first thing I worked with was viruses. And as I was studying viruses, I became interested in tackling bigger issues and exploring the unknown. In fact, less than 0.1 percent of all viruses are currently known to humankind. When I learned that 99.9 percent have yet to be discovered, I knew that this was the area I wanted to pursue, as it satisfied my impulse for exploring the unknown while also holding the potential for solving significant issues for human beings and animals.

Preparing for domestic and international risks

In a country like Japan, where sanitary conditions are quite good, we don’t usually associate insects with spreading diseases.

There’s an interesting background to that. As Japan developed in the postwar period, sanitary conditions improved, vaccines were developed, and the risk of vector-borne diseases dropped. Nobody thought about them anymore. Research in the field was scaled back to the point where, today, you would be hard-pressed to find a research lab in Japan that specializes in vector-borne diseases. The demand for sanitary entomology as a field of research had essentially dried up.

The recent uptick in inbound tourism, however, has made it easier for infectious diseases to enter Japan from abroad. COVID-19 is an example still fresh in our memory. At my lab, we investigate the risk of infectious diseases from other countries entering Japan. We also focus our research into how many existing viruses in Japan have yet to be discovered.

Does that mean you often collaborate with researchers overseas?

Yes, that's right. For example, we collaborate with institutions in China that specialize in infectious diseases to exchange information and identify risks associated with new infectious diseases and unknown viruses. We anticipate potential threats these viruses may pose and work together to consider preventive measures. For instance, if such a virus emerges in China, we discuss the likelihood of it spreading to Japan and how best to respond.

Seamless integration from fieldwork to data analysis

Could you tell us more about your research and what sets it apart?

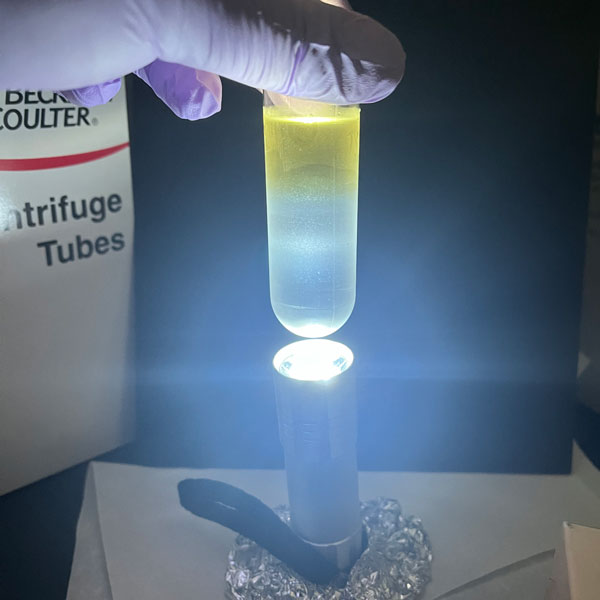

I would say our strength lies in our ability to discover new viruses. Living creatures of all kinds have viruses that we know nothing about, and our work involves finding them, isolating them, and analyzing how they work. First, we collect samples from target insects and animals in the field. Then, back in the lab, we do experiments at the molecular or cellular level and apply informatics to analyze the data we have obtained. Few other labs can seamlessly carry out this entire process.

How do you collect insect and animal samples?

I have a trapping license, so we might go into the mountains to trap animals and collect insects from their bodies. More often, though, we collect insects in urban areas and parks— anywhere people frequently encounter them. We also focus on infectious diseases in livestock, so we sometimes collect samples around barns and livestock enclosures.

It is easy enough to imagine trapping animals in the mountains, but how do you catch mosquitoes?

That’s easy. All you have to do is go to a park wearing a short-sleeve shirt with your skin exposed and stand there. You will attract mosquitoes, so all you need to do is catch them with an insect net (laughs). Basically, most of the insects we are targeting will approach people and animals, so catching them is easy.

How to connect basic research with real-world situations

Can you share any memorable stories from your research to date?

One of the most eye-opening moments for me was when I started working in the field of nanobiology, which involves examining the unique traits of genes and molecules inside cells at a more microscopic level. Organisms exhibit complex behaviors, but when you break everything down, their essential logic becomes apparent. My academic advisor at the time stressed the importance of logical thinking in research, and I continue to value that approach to this day.

I also spent some time in a medical research laboratory, where I conducted animal experiments and did some clinical work. While basic research conducted in a laboratory tends to be detached from the real world, clinical work is more closely connected. Learning how to bridge the gap between basic research and its real-world issues was a significant learning experience for me.

Experience helps reveal your interests and strengths

Do you communicate to your students the importance of both logic and practical considerations?

I try to convey that message, but it’s tough to put it all into practice from the start, so we first go out together to collect insects. Then we return to the lab and do experiments at the cellular level. That way, they get a wide range of experiences under their belt. Through this process, they can discover their interests and strengths, which is where I think they should focus their efforts.

What kind of people do you want your students to become?

Each student has different aspirations and ambitions for how they want to succeed in society, so I don’t have any particular expectations for what they should become. That said, I do want them to gain experience from their time as researchers here and learn to consider issues facing society and be able to act on them independently. I would like them to succeed in any field they choose, as long as it’s a path they have chosen for themselves.

Pursuing personal passions while addressing societal issues

On a personal note, what are your future plans and goals?

Research in the field of vector-borne diseases has been gradually declining in Japan. There’s a possibility that we won’t have enough qualified people to respond when a problem eventually arises. The risk of infectious diseases being brought in from overseas is likely to increase as climate change and globalization progress. I hope to inspire more students to take an interest in vector-borne diseases and cultivate talent that can excel in this field.

On a personal level, I am eager to shed light on viruses that have yet to be studied. There is no better feeling than the moment when I unravel a mystery that no one else has yet explained. Since the field of infectious diseases directly impacts public health, I am eager to pursue my personal passions while addressing societal issues.

Lastly, do you have any advice for middle school and high school students who may be unsure of what to do next?

I would say explore a lot of different things. The interests you have depend on what you can see with the knowledge you have at the time. The truly fascinating things are often found in places you haven’t explored or looked at before. While it’s important to have things you like and are good at, it’s often the case that things turn out differently than you first imagined. It’s hard to see what is truly interesting about something at first, so I encourage those of you with a particular interest to also look at other things and value learning across a broad range of subjects.

Visit Sanitary Entomology Labfor more information about his research.