A race against time: The challenge of preserving languages before they vanish

Discover the Research: Article 8 – Natsuko Nakagawa, Faculty of Humanities

As local languages continue to disappear, Associate Professor Natsuko Nakagawa from the Faculty of Humanities is dedicated to documenting and preserving them while uncovering the linguistic principles hidden within. She also harnesses digital technology, collaborating closely with local communities to ensure the transmission of their language and culture. We spoke with Nakagawa about the allure of linguistics and the field of digital humanities.

Exploring the hidden rules of language

Could you tell us about your research?

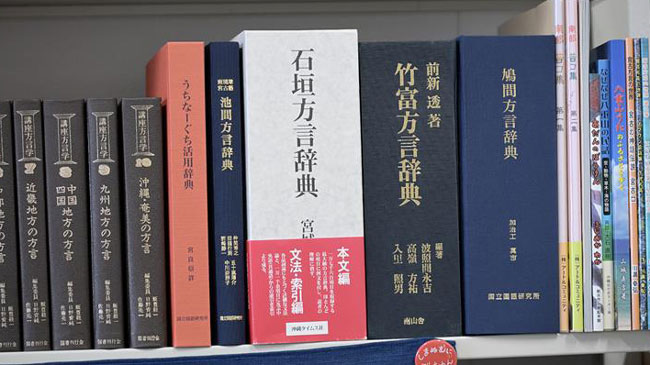

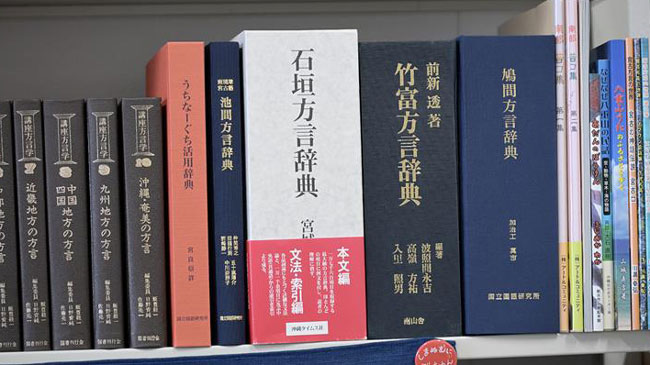

I specialize in the study of Japanese dialects. While my ambition is to explore all the languages spoken in Japan, my current research focuses on the southern Tohoku dialects from Japan’s northeastern region, and the Ryukyuan languages of the subtropical island chain stretching southwest from mainland Japan. I am concentrating on Yaeyaman, the language spoken in Japan’s most remote islands at the far southwestern tip.

Dialect research covers a wide range of areas, including pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary. My focus is primarily on grammar and pronunciation. I’m particularly intrigued by the mechanisms through which languages emerge, evolve, and transform. At present, my research centers on case particles—words like “wa” in watashi wa or “ga” in watashi ga—which indicate the grammatical role of a noun in a sentence, such as the topic or subject.

Could you explain what the Ryukyuan languages are?

These refer to the languages spoken in Okinawa Prefecture and the Amami Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture. They include Yaeyaman and Miyakoan, which are classified as Southern Ryukyuan, as well as the languages of the Okinawa main island, which belong to the Northern Ryukyuan group.

The Ryukyuan languages exhibit remarkable diversity, with substantial differences in vocabulary, grammar, and intonation from one island to another. For this reason, we refer to them in the plural—the Ryukyuan languages—to emphasize their multiplicity. Given the vast regional differences and distinctness from Japanese, we linguists argue that they should be recognized as independent languages rather than mere dialects.

How different are they from Japanese dialects?

They are worlds apart! People from Okinawa and mainland Japan can be totally lost trying to understand each other!

For instance, I am currently conducting research on Taketomi Island, located in the Southern Ryukyus. The local language there is known as Teedun Muni: teedun meaning “Taketomi” and muni meaning “language.” There are also sounds that begin with a syllabic nasal (like “n”) or a glottal stop (known in Japanese linguistics as sokuon, marked by a small “tsu”). These types of initial sounds do not occur in standard Japanese.

What sparked your interest in studying the Ryukyuan languages?

I’ve always loved islands. Interestingly, Southern Ryukyuan languages still retain certain grammatical features that have disappeared from modern Japanese. One such structure is kakarimusubi, a classical construction where sentence-ending forms are determined by earlier particles. I’m eager to explore this phenomenon in greater depth.

How do you conduct your research?

So far, I have followed traditional linguistic methods in my research. Specifically, I travel to various regions across Japan, prepare questions like “How would you say this in your dialect?” and conduct audio and video recordings.

Using a dialect is like riding a bicycle: it comes naturally to speakers but breaking down how it works isn’t always easy. That’s why, when speaking with local people, I carefully consider the context and repeatedly ask a series of questions about whether they would or wouldn’t use certain expressions in specific situations. Through this process, I form hypotheses and gradually uncover the knowledge embedded in the speakers’ minds, allowing me to compare and analyze their regional grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation.

However, I have recently been thinking about adopting a slightly different approach. Instead of formal interviews, I am considering just letting local people talk freely, like meaningful events and personal stories from their lives, and record their natural way of speaking in everyday conversation.

Preserving the future of dialects

According to a UNESCO report, Yaeyaman is in danger of disappearing.

Yes, that’s right. UNESCO has classified Yaeyaman as “severely endangered.” One of the key criteria for their determination is whether the language is still being passed down to younger generations. Unfortunately, Yaeyaman, along with other Ryukyuan languages, and even many dialects in mainland Japan, is now rarely spoken by young people. As a result, all these languages are considered at serious risk of disappearing.

For many speakers of Ryukyuan languages, it is common to use Japanese when speaking to babies. The daily speakers of the local languages are primarily those in their seventies or eighties. If this trend continues, once the elderly speakers are gone, the younger generations may be left speaking only Japanese. In addition, the situation is exacerbated by the influence of newspapers and television, which reduce both exposure to dialects and opportunities for education in these languages.

On the other hand, many people still understand the languages, and some have even begun actively learning them. This gives rise to a more optimistic view that these languages will not completely vanish anytime soon.

What are some of the ways you are trying to protect the future of dialects?

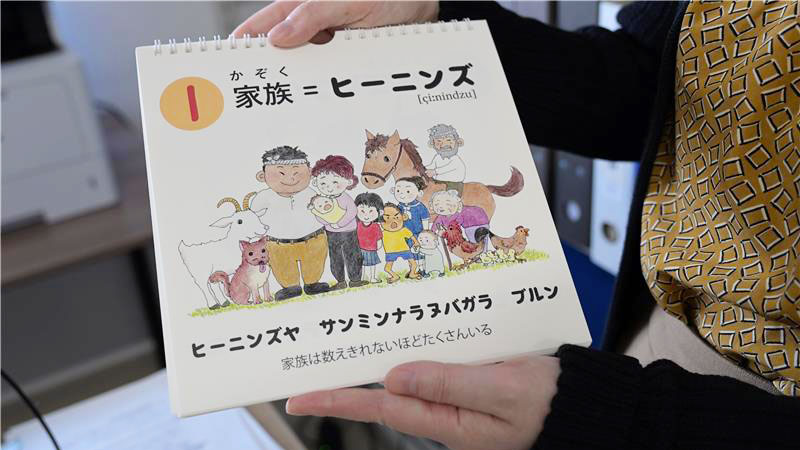

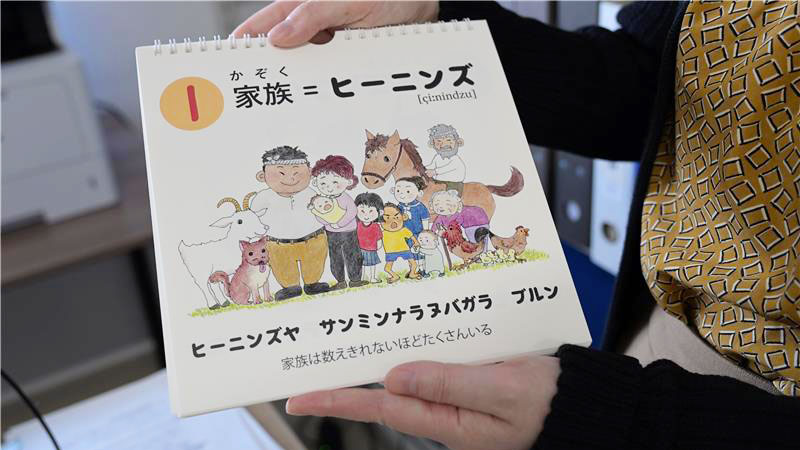

As linguists, it is not our place to dictate whether people should use their dialects daily. However, I do hope that opportunities to speak these languages continue to grow. Alongside my research, I have collaborated with researchers and illustrators to create works such as picture books based on local folktales. I have also worked in cooperation with community members to organize reading events and other initiatives aimed at preserving and passing on local culture.

Still, what matters most is undoubtedly the tireless dedication of the local people themselves. On Taketomi Island, for example, the Teedun Muni contest—a local language competition—has been held over 50 times to date. Participants range from preschool children to ninth graders, and through their diligent practice, many have become fluent speakers. It is through efforts like these that I truly feel the community’s enthusiasm for preserving their cultural heritage.

Why is it important to study and preserve dialects?

Dialects are precious cultural assets, encapsulating a region’s history, traditions, and the wisdom of its people. As a speaker of the Kansai dialect, the thought of losing my own language feels like losing a part of myself. Language is deeply tied to who we are, and everyone should have the freedom to speak their dialect proudly, without fear of ridicule.

Furthermore, it is essential to preserve proper documentation and records so these dialects can be relearned by anyone who wants to speak them. By studying and preserving dialects, we ensure future generations can experience their local culture through the words that truly belong to them.

Connecting society through language and digital technology

We’ve heard the term “digital humanities” before. Could you explain it in a bit more detail?

Sure. Put simply, digital humanities is an interdisciplinary field that uses digital technology to explore and answer questions in the humanities—things like language, history, literature, and culture.

In my own linguistic research, for instance, digital data forms the backbone of the entire process. From initial recordings to transcription and translation, every step is carried out using digital technologies.

How have technological innovations changed the study of language?

We can handle vast amounts of data far more efficiently now. In the past, manually reviewing each piece of linguistic data was extremely time-consuming. Now, even if I have hundreds of hours of recordings, I can quickly locate and extract specific linguistic expressions.

And it is not only about finding things faster. Linguistic analysis requires annotation, for example, tagging whether a noun refers to a living being or not. Thanks to the rapid evolution of AI, annotation work in particular has become significantly faster.

Generative AI has opened up even more possibilities. Materials that were once only decipherable by language specialists, like handwritten historical texts or academic papers in foreign languages, are now within reach of the general public. This increased accessibility also benefits learners, expanding their opportunities to engage with and explore new knowledge.

Kyushu University is opening a new Joint Graduate School of Digital Humanities. What kind of qualities or values do you hope your students will develop?

Kyushu University launched the Joint Graduate School of Digital Humanities in April 2025. We are seeking students who are curious about humanities-driven questions and eager to explore digital technologies.

That said, I really hope they do not feel like they have to live up to society’s idea of being “useful.” Honestly, I don’t think that mindset truly leads to greater happiness for society as a whole. Instead, I believe happiness comes from being yourself, studying what excites you, and pursuing what you are genuinely interested in.

Could you share your outlook for future research?

While my primary focus is dialect research, I would like to collaborate with scholars in a range of fields like history, cultural anthropology, informatics, and beyond.

Lately, I have become increasingly interested in the potential of AI in unraveling language mechanisms. I am especially intrigued by how generative AI can “speak” so fluently and would love to explore further.

As for my linguistic research, I want to deepen my collaboration with local communities, gathering their stories, and recording their regional history and culture in greater depth. Eventually, I hope to use digital tools to return the collected data to the communities, preserving it as a shared cultural resource for future generations.

Lastly, do you have any advice for junior or senior high school students who are unsure about their future path?

I think it is a wonderful thing to find something that sparks your curiosity. And once you do, I hope you will enjoy seeing where it takes you.

Visit Nakagawa’s lab for more information about his research.