© JAXA

Exploring the Mysteries of

Ryugu from Kyushu

Commemorating Hayabusa2’s Return to Earth

Professor

Hiroshi Naraoka

Faculty of Science,

Kyushu University

Kyushu University

Professor

Takaaki Noguchi

Faculty of Arts and Science,

Kyushu University

Kyushu University

The Hayabusa2 spacecraft, which was launched from Tanegashima Space Center on December 3, 2014, safely completed its mission and returned to Earth on December 6, 2020. Initial analysis of samples brought back by Hayabusa2 from the asteroid Ryugu is currently underway by six international teams, three of which are being led by professors at Kyushu University. Here, we sat down with professors Takaaki Noguchi and Hiroshi Naraoka, who both worked on the first Hayabusa spacecraft and are now involved in the initial analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples.

© JAXA

Exploring the

Mysteries of

Ryugu from

Kyushu

Commemorating Hayabusa2’s Return to Earth

Professor

Hiroshi Naraoka

Faculty of Science,

Kyushu University

Kyushu University

Professor

Takaaki Noguchi

Faculty of Arts and Science,

Kyushu University

Kyushu University

The Hayabusa2 spacecraft, which was launched from Tanegashima Space Center on December 3, 2014, safely completed its mission and returned to Earth on December 6, 2020. Initial analysis of samples brought back by Hayabusa2 from the asteroid Ryugu is currently underway by six international teams, three of which are being led by professors at Kyushu University. Here, we sat down with professors Takaaki Noguchi and Hiroshi Naraoka, who both worked on the first Hayabusa spacecraft and are now involved in the initial analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples.

Footage of the Apollo 11 Moon landing inspires dreams of space

When did you first become interested in space?

Noguchi When the Apollo spacecraft landed on the moon. I was eight years old at the time, and at school, we would all stick rulers out of our backpacks and pretend like we were astronauts on the moon. [laughs] I was initially interested in rocket launches, but when I was in junior high and high school, there were a series of space probe launches—Pioneer, Viking, Voyager—and seeing images from those missions made me think that it would be more interesting to study the asteroids themselves. That’s what led me to where I am today.

Hiroshi Naraoka

Professor, Faculty of Science

Naraoka I was also very much inspired by Apollo 11. I was in elementary school, and our teacher brought a TV to the classroom so we could all watch it together. Thinking about it now, that was a good education. Also, I grew up in a rural area, and when I was a kid, you could see the Milky Way when you looked up at the night sky. It was profoundly beautiful, and I knew I wanted to study something related to space. If it hadn’t been for those starry skies, I might not have ended up choosing this career.

Hard to handle: The fine grains of the Hayabusa samples

You also conducted the initial analysis of samples brought back by the first Hayabusa mission, correct?

Noguchi I was actually involved from the curation process that precedes the initial analysis. Curation is the process of receiving the samples and handing their initial description, distribution, storage, and management. Samples from Hayabusa returned to Earth in June 2010, but we had been preparing to receive them at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center in Sagamihara since September of the previous year. The original plan was to analyze much larger samples, but it turned out that we were only getting sand-like particles of a few tens of microns, so we had to build a device to extract the particles without contaminating them. Once we did that, we were able to retrieve some samples, but we didn’t find any critical particles for another three months, which was certainly a low point in our curation.

Takaaki Noguchi

Professor, Faculty of Arts and Science

Naraoka The largest particle was only 300 microns, wasn’t it?

Noguchi That’s right. Since it was difficult to find minute particles, we decided to try turning the container over. When we flipped it upside down and gave it a tap, out fell particles so large that you could see them with the naked eye. [laughs] We were able to collect dozens of samples at once and were finally able to distribute the samples to researchers across Japan. We finished distributing the samples in mid-January 2011 and hurried to begin our initial analysis as we were scheduled to present our first results at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in March.

Naraoka I, too, ended up going to Sagamihara to receive samples, and it took two days just to pick up five samples. When you try to put one in a container, it bounces around because of the static electricity. The analysis was also done on a sort of assembly line, so as soon as we received a sample, we had to analyze it and hand it off to the next person, which was quite hectic.

Kyushu U

Knowledge

From Hayabusa to Hayabusa2

The asteroid probe Hayabusa2 was launched in December 2014 and returned to Earth on December 6, 2020. Hayabusa2’s mission was a sample-return mission, which collects samples from the surface of an asteroid and brings them back to Earth, continuing the original Hayabusa mission launched in 2003.

| Hayabusa | Hayabusa2 | |

| Mission | Engineering: Demonstration of engineering (sample return technology) required for deep space round-trip exploration. | Science: Study of the origin and evolution of the solar system and the evolution of the building blocks of life using returned samples from a C-type asteroid. |

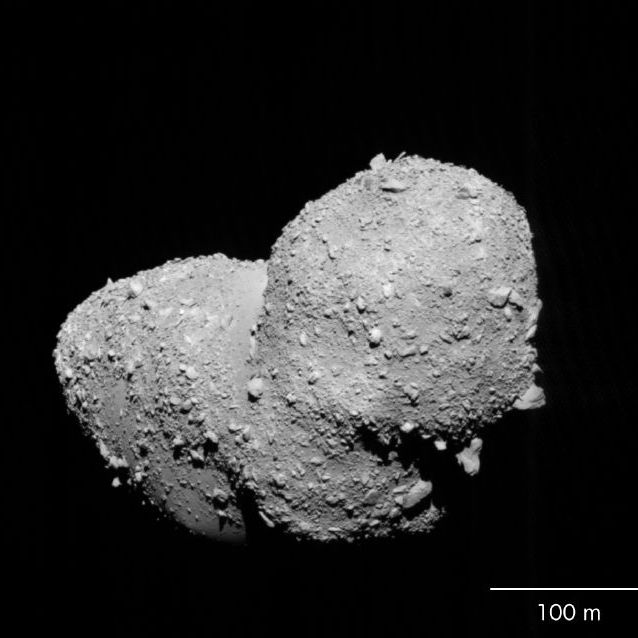

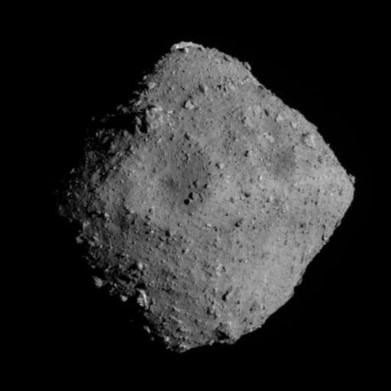

| Target body | Itokawa: An S-type asteroid that holds information on the evolutionary process of the terrestrial planets. | Ryugu: A C-type asteroid that retains information on the early formation of the solar system and contains a large amount of organic matter (carbon-containing compounds) and water, which are building blocks of life. |

Itokawa

© JAXA, The University of Tokyo, et al. |

Ryugu

© JAXA |

Scroll for more →

This is just one example of Kyushu University excellence.

This is just one example of Kyushu University excellence.

© JAXA

© JAXA

Samples returned by Hayabusa2: Expecting the unexpected

What kind of results came out of the initial analysis of the original Hayabusa samples?

Noguchi It was my job to conduct observation and analysis of samples using an electron microscope to determine what was inside the particles and how their surface gradually changes. We call this “space weathering,” the process by which rocks and minerals are altered after being exposed to space for long periods of time, which we were able to see at the material level. Also, in March this year, in collaboration with JSPS Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Toru Matsumoto, we discovered a single iron crystal with a whisker-like growth on the surface of dust particles brought back by Itokawa, something still unknown in extraterrestrial materials. I believe that it will be an important insight into the history of the surface of asteroids like Ryugu. Professor Naraoka, what did you think?

Photo taken just after the first Itokawa particles were discovered at the Sample Curation Facility of JAXA. Front, from left: Dr. Tomoki Nakamura, Tohoku University; Professor Takaaki Noguchi, Kyushu University. Back, from left: Associate Professor Takashi Okazaki, Kyushu University; Masanao Abe, JAXA; and Akio Fujimura, then Director of the JAXA Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center.

Naraoka Well, my specialty is organics, and Itokawa was an S-type asteroid with no organic matter. Nevertheless, there was meaning in the very process of checking for the presence of organic matter. Despite the analysis we conducted, so far, no organic matter has been found.

Hayabusa2’s target body, Ryugu, is a C-type asteroid that contains organic matter, which must be very exciting.

Naraoka That’s right. When a meteor enters the atmosphere, the material on the surface gets peeled away, but the samples brought back by Hayabusa2 will still have that surface material intact, so I am hoping that we will be able to find something that we have never seen before.

There are reports that you were able to collect samples, not only from Ryugu’s surface, but also from the bottom of an artificial crater.

Naraoka Asteroids are exposed to cosmic rays, which are high-energy particles, so I think the organic matter on an asteroid’s surface is in a rather precarious position. If we are able to collect material from areas not affected by cosmic rays, we may find something unexpected—the original organic material of the asteroid

The samples brought back by Hayabusa2 will be analyzed at this cleanroom, which was recently installed in the Faculty of Science at Kyushu University. Professor Naraoka at center.

Professor Noguchi, what are your expectations for the samples?

Noguchi There are hydrous minerals on Ryugu, but it will depend on whether they are merely minerals that contain water, water-containing minerals that have been dehydrated, or minerals that have not yet reacted with water.

Naraoka It would be great to find material that has never reacted with water.

Noguchi It would. The samples should contain primordial organic matter, and I think that we will see some rather unexpected results. Some people say that we shouldn’t expect much because an asteroid’s surface is warmed by solar radiation, but the results of rock samples from Ryugu observed by the French-German MASCOT lander ended up defying expectations. So I still think that we should expect the unexpected.

Valuing curiosity and finding your calling

It is said that people are shaped by their environment. In what ways is Kyushu University equipped to excel in space exploration?

Noguchi Well, Kyushu University has a number of electron microscopes on par with those used by leading international researchers. For more than ten years now, the university has been lending these high-performance electron microscopes to researchers across the country, and in a sense, this is quite a state-of-the-art environment. We also have new processing equipment scheduled to be installed at the Faculty of Engineering Sciences this year. If we can take full advantage of this equipment, it will allow us to receive Hayabusa2 samples and look at them under an electron microscope without them ever being exposed to the atmosphere. I think that the unique environment here at Kyushu University will allow us to achieve better results.

Kyushu U

Knowledge

Trajectories of Hayabusa and Hayabusa2

Hayabusa

2003.05

Launch of the original Hayabusa spacecraft

2009.09

Curation team begins preparing for analysis

2010.06

Original Hayabusa mission returns to Earth and dust particles are collected

2010.11

Collected dust particles are announced to indeed be from Itokawa

2010.12–2011.01

Particles for initial analysis are provided to researchers in Japan and initial analysis begins

2011.03

Presentation of the initial analysis results at the 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference

Hayabusa2

2014.12

Launch from Tanegashima Space Center

2018.06

Arrival near asteroid Ryugu

2018.09

Separation, landing, and operation of the small asteroid lander MASCOT

2019.02

First touchdown

2019.07

Second touchdown

2019.11

Departure from Ryugu and start of journey home

2020.12.6

Re-entry capsule returns to Earth

2021.06–

Initial analysis scheduled to begin

Naraoka Although he could not join us today, Associate Professor Takashi Okazaki of the Kyushu University Faculty of Science is also leading one of the teams handling the initial analysis of Hayabusa2 samples. Four faculty members from Kyushu University, including Associate Professor Okazaki, are involved in the analysis of Hayabusa2 samples, and several graduate students are also participating in the research. A number of JAXA researchers and technicians are also Kyushu University graduates. I believe that these professionals and what they have accomplished are one of Kyushu University’s advantages.

Lastly, do you have a message to all of the students here at Kyushu University?

Naraoka In addition to Hayabusa2, there are many other space programs currently underway, so we have a lot to look forward to. But that kind of progress relies on the hard work of researchers focused on what is in front of them. If you don’t enjoy your work, you won’t make progress in your research. I hope that students will stay curious to keep their research going.

Noguchi Whatever your specialty, I think it is essential, as a scientific researcher, to be able to focus on one thing. While you are still a student, I hope you will find your calling—the one thing you want to become an expert in—and make it your life’s work. I encourage you to find it while you’re a student at Kyushu University before you head out into the world.

This interview was conducted on October 7, 2020, in the Exhibition and Observation Room of the Ishigahara Tumulus, located on the 9th floor of East Zone 1 on Kyushu University’s Ito Campus. Associate Professor Takashi Okazaki of the Kyushu University Faculty of Science is also leading one of the teams in charge of the initial analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples but could not join us as he was busy preparing for the recovery of the Hayabusa2 capsule.

This article first appeared in the Dec. 2020 issue of Kyushu University Campus Magazine (九大広報), the university's quarterly Japanese-language magazine. View the full issue online for more information in Japanese about the recent happenings at Kyushu University.

This article first appeared in the Dec. 2020 issue of Kyushu University Campus Magazine (九大広報), the university's quarterly Japanese-language magazine. View the full issue online for more information in Japanese about the recent happenings at Kyushu University.