研究成果 Research Results

- TOP

- News

- Research Results

- Revisiting what defines hikikomori as cases rise internationally

Revisiting what defines hikikomori as cases rise internationally

2020.04.02Research ResultsHumanities & Social SciencesLife & Health

Critical to being able to treat a condition, especially in the field of psychiatry, is the ability to first diagnose it. To that end, researchers from Kyushu University in collaboration with the Oregon Health & Science University have now proposed updated criteria for a form of social withdrawal called “hikikomori” with the hope of standardizing evaluation and improving response in the future.

Hikikomori has been strongly associated with Japan as increasing cases of adolescents staying at home—sometimes in a single room—and avoiding social activities such as school and work since the late 1990s began to gain national attention. However, reports of hikikomori-like cases from around the world have indicated that hikikomori is not isolated to one culture or country and is an international issue.

To better understand, define, and treat the condition, Takahiro Kato and his colleagues established the Mood Disorder/Hikikomori Research Clinic at the Kyushu University Hospital, where they have been working with patients suffering from hikikomori and their families and developing new methods of support.

“Since the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare issued some of the early guidelines for diagnosing hikikomori in 2010, we have made tremendous progress in understanding the common characteristics among those with the condition,” says Kato.

“In addition, we have identified several points of confusion in the early guidelines and have proposed a new set of diagnostic criteria for hikikomori that better reflect our current understanding for international acceptance.”

At the core of the new criteria, which were published this January in World Psychiatry, is social isolation in one’s home for a duration of more than six months accompanied with significant functional impairment or distress stemming from the isolation.

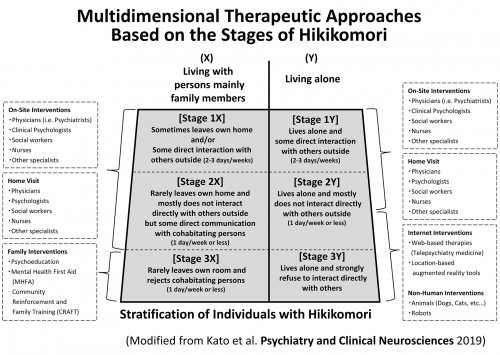

The new definition gives further guidance on the severity of social isolation, with hikikomori being classified as mild, moderate, or severe depending on whether the person leaves home up to three days a week, leaves home one or less days per week, or rarely leaves a single room.

Missing from these criteria is an avoidance of social situations.

“Talking to those with hikikomori, we often hear that avoiding social interaction is not an underlying motive, which may distinguish hikikomori from social anxiety disorder,” notes Kato.

This definition also acknowledges that hikikomori can co-exist with other psychiatric disorders. Previous guidelines have excluded hikikomori from being diagnosed if other conditions are present, but the researchers have found that co-occurrence is quite common.

Furthermore, the researchers recommend that similar social isolation lasting for between three to six months as being classified as pre-hikikomori.

“By adding the ‘pre-hikikomori’ status to the evaluation criteria, we expect that a new support system for early prevention will be established,” says Kato.

The researchers hope that these criteria will allow people to more easily evaluate if someone is in a withdrawal situation that requires assistance. In addition, they expect that providing appropriate support based on each individual's condition will become easier using the additional specifiers they proposed for further characterizing individual cases of hikikomori.

“By using these criteria in international epidemiological surveys to understand the phenomenon of youth hikikomori as it spreads overseas, we expect that a better picture of the internationalization of hikikomori and the global problem of social isolation will emerge,” states Kato.

For more information about this research, see “Defining pathological social withdrawal: proposed diagnostic criteria for hikikomori,” Takahiro A. Kato, Shigenobu Kanba, and Alan R. Teo, World Psychiatry, 19(1), 116–117, 2020 Feb, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20705

Also, see “Hikikomori: Multidimensional understanding, assessment and future international perspectives,” Takahiro A. Kato, Shigenobu Kanba, and Alan R. Teo, Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 73(8):427–440, 2019 Aug, https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12895

This research is supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), with the support of the Research and Development Program for Persons with Disabilities and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology's Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) on Innovative Areas for "Will Dynamics."

Fig. 1. Chart showing the different therapeutic approaches for hikikomori depending on the stage of the condition.

Journal Reference

Defining pathological social withdrawal: proposed diagnostic criteria for hikikomori, ,World Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20705Research-related inquiries

- TOP

- News

- Research Results

- Revisiting what defines hikikomori as cases rise internationally